Displaying items by tag: Longs Peak

Colorado's 12 Hardest 14ers to Climb

Colorado's Fourteeners (14ers) are legendary. Each of the 53 ranked peaks offers unique challenges and rewards. They are the some of the most amazing mountains in the world and have been the number one object of adoration for hundreds of thousands of Coloradoans. Indeed, according to the Colorado Fourteeners Initiative (CFI), approximately half a million people attempt to climb a fourteener each year. Climbing 14ers is a dangerous activity; however, good planning, fitness, and awareness of the potential hazards will provide climbers with good opportunities to accomplish these monsterous peaks. Each year I'm usually asked one of two questions - which 14ers are the easiest; and, which 14ers are the hardest? I decided to lay out the hardest 14ers here for you in this article. Let me know how I did based on your own experience. Lastly, it might be a good idea to arm yourself with the most up-to-date information about mountaineering accidents in Colorado. Who knows, reading about these tragic events may just save your life. Additionally, I highly recommend obtaining GaiaGPS for your phone. It allows you to see your track and location on a USGS map overlay even in airplane mode. It has saved me so many times. You can purchase it here and help support the site.

While it may make sense to simply use the only existing data available regarding mountaineering accidents in Colorado to determine 14er difficulty, my experience has been that the difficulty of a peak is more than just cold, hard facts. Indeed, Longs Peak is not nearly as difficult as, say, Capitol Peak; however, it has far more accidents due to the sheer number of inexperienced and/or unaccomplished people attempting it each year. With that being said, I'm going to use a mixture of my personal experience and some subjective ratings to present my case to you. For these ratings it is assumed that the climber is approaching via the standard route in "normal" conditions. I've intentionally left out un-ranked 14ers such as North Maroon and El Diente - assume they can be bundled with Maroon Peak and Mount Wilson, respectively. Additionally, consideration of any traverses between 14ers was not considered for these ratings.

I will rate each mountain's difficulty ranking based on four equally weighted variables:

1. Sustained difficulty: this rating establishes the peak's sustained difficulty over the course of the entire climb

2. Most difficult section: this rating establishes the difficulty of the peak's most difficult section

3. Terrain: this rating establishes the difficulty of the peak's overall terrain, taking exposure and looseness of rock into account

4. Access: this rating establishes the difficulty to reach this peak or how long it takes to get to the top

Feel free to let me know if you disagree with my ratings!

#1. Capitol Peak

While Capitol Peak has only seen two deaths since 2010 compared to five on Longs Peak (as of August 2014), it is arguably the most difficult 14er in Colorado, as I attested in my 2010 trip report. As pictured above in the panoramic taken between Capitol Peak and K2 near the infamous Knife Edge, the terrain is rugged, exposed, loose and dangerous. Not only does Capitol Peak have some very difficult sections, it has, in my opinion, the highest sustained difficulty out of any of the 14ers. The climb up Capitol is relentless and requires mountainners to focus on the mountain's terrain for a very long period of time. There are very few breaks to be had and simple mistakes can and do prove to be fatal. Additionally, Capitol Peak requires a lot of time to accomplish and once you are past the knife edge, you are committed to at least two hours more of climbing. This makes the mountain especially mentally taxing as those are two hours straight of focused climbing on rugged terrain where you also have to keep a keen eye on the weather. Lastly, access to Capitol, while doable in a single day, usually requires an arduous backpacking trip to Capitol Lake and a very early start on a subsequent day. Let's see how Capitol Peak rates in the four domains:

| Sustained Difficulty: 10/10 | |

| Most difficult section: 9/10 | |

| Terrain: 10/10 | |

| Access: 9/10 | |

| Total: 38/40 |

#2. Mount Wilson

Mount Wilson is easily one of the most challenging 14ers in Colorado to climb - the standard route, while mostly straight-forward, has many difficult sections of very loose rock at the summit. The summit block itself has stopped many people in their tracks, just a few feet from the summit. The exposure there is intense and not for the feint of heart. Examples of this can be seen in my trip report from 2011. In addition to the tremendous exposure found on the summit block, Mount Wilson's approach from the Rock of Ages trailhead is fairly long and quite committing, with a lot of up-and-down climbing (unless approached from Kilpacker Basin or Navajo Basin). The difficult section of climbing found on the upper 1/3 of the route is difficult to negotiate and offers many challenges for climbers of all levels. The rock on Mount Wilson is extremely loose and many people have perished on the slopes between Mount Wilson and the un-ranked beast to the west - El Diente.

| Sustained Difficulty: 10/10 | |

| Most difficult section: 9/10 | |

| Terrain: 10/10 | |

| Access: 7/10 | |

| Total: 36/40 |

#3. Little Bear Peak

Out of all of the Fourteeners, Little Bear Peak is quite possibly my least favorite and least likely to be something I'd like to repeat. The approach is terrible - either a long slog on a rocky road in hot weather or an insane jeep ride over some of Colorado's toughest jeep obstacles (OK - those are kind of awesome). My ascent in 2010 was quite memorable, notably - the infamous "Hourglass" section just about scared me to death. Many people have perished in the Hourglass over the years, including one of the most memorable deaths in the past 5 years - Kevin Hayne. The Hourglass presents some very difficult climbing, with few good hand-holds and potentially fatal ice and water sections, not to mention the hazard of frequent rockfall from above. While Little Bear Peak is very straight-forward and mostly an easy climb, the Hourglass section marks it as one of the toughest mountains around.

| Sustained Difficulty: 6/10 | |

| Most difficult section: 10/10 | |

| Terrain: 10/10 | |

| Access: 7/10 | |

| Total: 33/40 |

#4. Pyramid Peak

Pyramid Peak, while not having many known fatalities, presents some truly heinous climbing obstacles, especially in wet conditions. The rock in the Elk Mountains is notoriously loose and nasty - making it very suspect in down-climbs and even more dangerous in rain or snow. The approach to Pyramid is fairly straightforward, albeit somewhat long and committing once above tree-line. The terrain on Pyramid is steep almost the entire climb and once above tree-line the mountain demands your concentration for the duration. While Pyramid is likely one of my favorite climbs of all time, it is not for a beginner climber and should be taking quite seriously. Of course, the views from the summit are to die for.

| Sustained Difficulty: 8/10 | |

| Most difficult section: 8/10 | |

| Terrain: 9/10 | |

| Access: 6/10 | |

| Total: 31/40 |

#5. Maroon Peak

The photo above was taken from the summit of Pyramid Peak looking out across the valley at the Maroon Bells and their insane stature. The whole area is steep and impressive, which comes with some inherent dangers and difficulties. The Maroon Bells have claimed many lives through the years and are certainly some of the most dangerous mountains in America. Of particular note, the traverse between Maroon Peak and North Maroon has claimed several victims and is a force to be reckoned with. Maroon Peak is a steep monstrosity full of beauty and loose rock as well as an intricate network of rocks, spires and falling rock that a blessing and a curse. Maroon Peak holds some of Colorado's worst rock and even the most experienced climbers have been subdued by the dangerous terrain found there.

| Sustained Difficulty: 8/10 | |

| Most difficult section: 8/10 | |

| Terrain: 9/10 | |

| Access: 6/10 | |

| Total: 30/40 |

#6. Snowmass Mountain

Snowmass Mountain is usually climbed in the early months of summer, when the face of the mountain is mostly covered in snow, making for somewhat easier travel up the snow in crampons; however, the rock beneath the snow is quite loose and is constantly shifting due to erosion. Indeed, Snowmass has proved to be particularly dangerous in the past few years due to these shifting conditions and has claimed a couple lives in the past 5 years. Snowmass' upper slopes contains large white boulders that look secure but are often quite loose and came come crashing down at any moment. The approach on all routes of Snowmass requires quite a bit of travel, which increases the difficulty.

| Sustained Difficulty: 8/10 | |

| Most difficult section: 6/10 | |

| Terrain: 7/10 | |

| Access: 8/10 | |

| Total: 29/40 |

#7. Sunlight Peak

Sunlight Peak is one of the few 14ers requiring class 4 climbing to reach the summit and is generally preceded by a very long backpacking trip and a steep ascent into the Twin Lake basin. Terrain in the Chicago Basin where Sunlight resides is notoriously loose and dangerous as well as highly susceptible to frequent and quickly changing extreme weather conditions. The summit block of Sunlight presents a particularly interesting challenge for climbers and many people skip the summit block altogether if there is any moisture on the rock. Many people may rate Sunlight's next door neighbor, Windom Peak, as being the more difficult of the two; however, I personally found Sunlight to have more challenging route-finding and climbing requirements. Since Sunlight is often paired with Eolus and Windom on the same day and often as the last peak climbed, it presents even more inherent danger as many climbers attempting it are more exhausted than if doing Sunlight on its own.

| Sustained Difficulty: 7/10 | |

| Most difficult section: 8/10 | |

| Terrain: 6/10 | |

| Access: 8/10 | |

| Total: 29/40 |

#8. Crestone Needle

Coming in at number 8 on my list of Colorado's most difficult 14ers to climb is the venerable, impressive and just-plain-freaking-awesome Crestone Needle - my favorite 14er of all. The standard route of Crestone Needle brings you up a steep approach and then plants you right in a series of difficult route-finding challenges and some of the steepest yet most solid rock there is. Even though the rock is quite solid and sturdy, make no mistake - an error in judgement would likly prove fatal, especially in severe weather conditions. Indeed, Crestone Needle has claimed many lives and is a surely one of the most dangerous peaks in the Sangre de Cristo Range. Most approachs require a backpack trip or a very early start and once above tree-line the terrain is quite extreme.

| Sustained Difficulty: 7/10 | |

| Most difficult section: 7/10 | |

| Terrain: 9/10 | |

| Access: 5/10 | |

| Total: 28/40 |

#9. Longs Peak

Longs Peak, located within the heart of Rocky Mountain National Park, is likely Colorado's most frequently visited mountain other than perhaps Greys and Torreys. This mountain's location in a National Park makes it a very popular destination by people from all over the world and it often lures inexperienced climbers on its more dangerous upper sections where people find themselves ill-equipped to complete the climb, both mentally and physically. Perhaps the most notable part of Longs Peak's approach is the sheer length of the climb, a full-day affair to be sure. A simple google search of Longs Peak deaths will just tell you how dangerous this peak really is, especially on the upper areas such as the Narrows and the Trough. Additional hazards plaguing this peak are the frequent deposits of snow and ice early and late in the climbing season that often contribute to the dangerous nature of the climb.

| Sustained Difficulty: 9/10 | |

| Most difficult section: 6/10 | |

| Terrain: 8/10 | |

| Access: 5/10 | |

| Total: 28/40 |

#10. Kit Carson Mountain

Kit Carson Mountain is one of the Sangre de Cristo giants located right by Crestone Peak and Crestone Needle. The approach to Kit Carson's standard route involves a lengthy backpacking trip and an ascent over the less impressive, albeit quite steep 14er, Challenger Point. The steep approach, coupled with a downclimb mired in confusion and difficult route-finding, makes Kit Carson quite eligible for this list. Several climbers have perished on Kit Carson in recent years, almost always due to off-route climbing.

| Sustained Difficulty: 8/10 | |

| Most difficult section: 6/10 | |

| Terrain: 6/10 | |

| Access: 7/10 | |

| Total: 27/40 |

#11. Mount Eolus

Mount Eolus marks the second of the Chicago Basin 14ers to make this list and arguably the more difficult of the three, despite my lower rating here. Eolus' "Catwalk" and steep, confusing route on the upper third of the mountain make it a top contender. The approach for Eolus is quite taxing as well and many climbers reaching the upper sections of Eolus find themselves out of energy and weakened - a terrible combination when paired with the rugged and loose terrain of the San Juan Mountains.

| Sustained Difficulty: 6/10 | |

| Most difficult section: 7/10 | |

| Terrain: 6/10 | |

| Access: 8/10 | |

| Total: 27/40 |

#12. Crestone Peak

Crestone Peak has single-handedly claimed many climbers' lives over the past several years due to the loose and difficult terrain found on the upper sections of the mountain. While the mountain's standard route is mostly straight-forward, there are certainly sections that demand one's full attention and good climbing skills in order to ensure a successful summit. Like Crestone Needle, Crestone Peak's approach is a very long day up very steep trails and rock formations, increasing the difficulty of this impressive peak found in the awesome Sangre de Cristo Mountains.

| Sustained Difficulty: 6/10 | |

| Most difficult section: 7/10 | |

| Terrain: 6/10 | |

| Access: 8/10 | |

| Total: 27/40 |

How did I do? Would you have rated them differently? How so? I'd love to hear your thoughts!

2013 Colorado Mountaineering Deaths - A Review

2010 Colorado Mountaineering Deaths - A Review and Remembrance

An in-depth review and analysis of every Colorado mountaineering death from 2010.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- Introduction

- Heidi Kloos – Baldy Peak (Ice Climb) - 3/30/2010

- Kevin Hayne - Little Bear Peak - Hourglass route - 6/15/2010

- Jeffrey R. Rosinski - Longs Peak - Keyhole Route - 7/15/2010

- Robert Doyle - Mount Cutler - 7/25/2010

- Peter Topp - El Diente Peak - 7/26/2010

- Duane and Linda Buhrmester - Crestone Needle - Ellingwood Arete route - 7/27/2010

- Spencer James Nelson - Maroon Bells - Bells Traverse - Bell Cord Couloir - 8/14/2010

- Benjamin Russell Hebb - Longs Peak - Diamond - Dunn-Westbay route - Broadway ledge - 8/27/2010

- Don Thurman - Kit Carson Mountain - 9/18/2010

- John Regan - Longs Peak - Keyhole route - 9/25/2010

- John Merrill - El Diente Peak - 9/26/2010

- James Nelson - Mount of the Holy Cross - 10/3/2010

- James Patrick - Taylor Peak and Powell Peak - Rocky Mountain National Park - 10/16/2010

- Chris Pruchnic - Thatchtop Mountain - 11/20/2010

- Summary / Data / Charts / Common Themes

2010 marked one of the deadliest years in Colorado history for mountaineers -15 deaths. While no entity keeps official records of mountaineering deaths in Colorado, the American Alpine Club publishes its annual Accidents in North American Mountaineering (ANAM) book, which highlights every known accident and death in North America as well as providing meaningful statistics, broken down by State and type of accident. The scope and purpose of that book is for mountaineers to read about accidents and to learn from them. Through analyzing what went wrong in each situation, ANAM gives experienced and beginning mountaineers the opportunity to learn from other climbers' mistakes. From inadequate protection, clothing, or equipment to inexperience, errors in judgment, and exceeding abilities, the mistakes recorded in the book are invaluable safety lessons for all climbers.

With that being said, I wanted to focus more on Colorado Mountaineering specifically, and provide my own respectful opinion on each death, as well as a remembrance for each victim. I am also hopeful that this website may serve as a historical reference for Colorado Mountaineering Accidents - at least 2010 and forward. I have tried to follow reasonable guidelines in analyzing each death. If you have information or data that contradicts or adds further clarity to one of the accidents described below, please feel free to This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

My personal philosophy is that each mistake, accident or unfortunate event has a valuable lesson attached to it. I also believe that even simple coincidences or freak accidents, where no fault can be laid upon the mountaineer, can be analyzed or studied. Perhaps in reading about one of these such accidents, other climbers may decide to avoid that mountain or take extra precautions when attempting to climb it. I am hopeful that if I were to perish from a mountaineering accident that others will study my actions to discover any possible errors I may have made that contributed to my demise, and share those errors with others for educational purposes. Additionally, most of us that climb mountains do so with the knowledge that it is dangerous and that accidents can and will occur. The only thing we can do to mitigate that risk is to educate ourselves, learn from others, and prepare as much as possible. My hope is that this work is a small means to that end.

In researching this topic, when possible, I have made attempts to contact family and friends of the deceased in order to obtain permission for photographs, etc.

Lastly, I want to leave the reader with a few quotes before I begin, in the hopes that they may impress upon the reader the true intent of this body of work:

- “Learn all you can from the mistakes of others. You won't have time to make them all yourself.” - Alfred Sheinwold

- “Mountains are not fair or unfair - they are just dangerous.” - Reinhold Messner

- “The mountains will always be there, the trick is to make sure you are too.” - Hervey Voge

1. Heidi Kloos – Baldy Peak (Ice Climb) - 3/30/2010

|

|

Photo courtesy of The American Alpine Club by Drew Ludwig |

Heidi Kloos was a 41-year-old Ridgway resident and well-known mountain guide. She was found buried under 10 feet of snow after she was caught by an avalanche near Baldy Peak, just east of Ridgway, CO.

Heidi was one of only a few female alpine guides certified by the American Mountain Guides Association. She had guided extensively around the world, and therefore one could assume that she was well trained and educated on proper avalanche precautions.

According to the Colorado Avalanche Information Center (CAIC), a website dedicated to providing avalanche infomation and education, Kloos was alone when she headed out to do a remote ice climb. After friends reported her missing, members of the Ouray Mountain Rescue Team were dispatched to the area.

Searchers found tracks leading into a large avalanche debris field measuring 150 by 80 meters. They also found Heidi's backpack and climbing gear, including an avalanche beacon, just outside the avalanche debris area at the base of a cliff wall.

According to CAIC, searchers presume that Kloos dropped her gear before heading up to assess the climb and en route was caught low in the path of the avalanche. Kloos' body was found with probes, buried 10 feet below the surface.

In 2008, she received the Denali National Park Service's Denali Pro Award for her efforts in assisting the National Park with a difficult rescue there in 2007.

Additionally, Kloos led guided trips in Antarctica and Argentina - she was clearly a well-trained and accomplished mountaineer.

For the official CAIC report of the incident, click HERE.

Analysis:

Because of her extensive experience and accomplishments, Heidi was clearly quite capable of climbing nearly any route she would have encountered. Some highly experienced mountaineers tend to take higher risks than less experienced mountaineers, due to their confidence and also because of the inherent rewards for success when risks are overcome. In some instances, the more experienced one becomes, the greater the challenge required to stimulate that sense of excitement and pursuit of reward. It is therefore reasonable to theorize that Heidi may have taken some unnecessary risks that led to the accident that killed her.

First, Heidi could have greatly benefited from having at least one other person with her for the trip into an avalanche prone area and the climb. Not only is this a common safety precaution for ice climbing, but it is also a common safety precaution for all back-country activity where avalanche danger is high. Travel into areas with high avalanche danger should always be with groups that are staggered (to avoid everyone from being buried at once). Everyone in the group should also be equipped with all of the proper avalanche safety equipment, including beacons, probes and shovels.

Due to her high skill level, it is reasonable to assume that Heidi had successfully soloed many similar ice climbs before without incident. Previous mountaineering success is a frequently correlated with higher risk taking - a cause that stems from psychological pitfalls.

Since Heidi was carrying an avalanche beacon, it is also reasonable to assume that she knew of the avalanche risks. Unfortunately, an avalanche beacon is of little use if no one is with you with probes and a shovel to rescue you. Lastly, Heidi had made the trip to this area prior to the accident, without incident, which may have caused her to believe it was safe to return to the area for climbing. It is unknown if snow conditions had changed between her visits to the area.

My deepest condolences and sympathy go out to Heidi's family and friends. Heidi's passing is a tremendous loss to the climbing world. A memorial scholarship fund was established through Mountain Trip for the Telluride Adaptive Sports Program. Donations in memory of Heidi Kloos may be made to TASP (contact Mountain Trip, 866-886-8747 or 970-369-1153), as well as to Ouray Mountain Rescue (970-318-8872).

2. Kevin Hayne - Little Bear Peak - Hourglass route - 6/15/2010

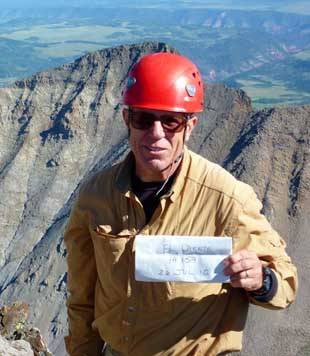

Photo courtsey of Lynn Hayne, taken on Kevin's way up Little Bear the day of the accident.

Kevin Hayne, an 18-year-old from Highlands Ranch, CO, died while attempting to climb the standard route of Little Bear Peak, known as the Hourglass. The Hourglass is a 4th class scramble - a very narrow gap between two towering cliffs comprised of very loose rock. Having climbed Little Bear's Hourglass myself, I can attest to the gritty and dangerous nature of this section of the mountain, and can personally say it was one of the more challenging mountaineering adventures I've been on. Here are three photos of the Hourglass, looking up and looking down, which demonstrate the sheer steepness of this section. In the first photo, you can see the loose rock just above me - this is where I believe Kevin fell from.

Kevin was accompanied by his friend, Travis Winder. The two reached the Hourglass and found it covered with a thin coating of ice. They decided to pass the Hourglass on its left, climbing across the broken cliffs as seen above. Just after they started climbing, Kevin slipped and fell down the rocky terrain. Travis posted a detailed account of those events on 14ers.com: "Today me and Kevin8020 were hiking the hourglass just shy of the summit of Little Bear Peak. The hourglass was completely iced over and was impassable, we decided to take a ledge on the left side of The Hourglass and decided to wait and see if the sun would help melt anything out. 30 seconds after this decision was made, Kevin's hand/foothold (I could not see all of him) broke loose and he fell several hundred yards down the mountain. When I got to him he was breathing heavily and both his arms looked broken, both of our spot trackers malfunctioned at a terrible time. I waited 30 minutes by chance that the distress signal did go out, tried to comfort Kevin, and after no response from either Kevin or SAR, I made the hardest decision of my life and had to hike out, leaving my partner behind."

By the time the Search and Rescue (SAR) team reached Kevin, he had already passed away.

Kevin was a very religious and spiritual person, as well as the class valedictorian of his senior high school class at Lutheran High School in Parker. At the time of Kevin's death, he had climbed 35 of Colorado's Fourteeners, making him a fairly accomplished mountaineer by most standards. Several 14ers.com members who had previously climbed with Kevin had nothing but good things to say about him as a person, and it is obvious that he will be greatly missed by family and friends.

Analysis:

Little Bear Peak is one of the most dangerous mountains in Colorado, as evidenced by an incomplete historical timeline of accidents on that mountain provided by John Kirk. The Hourglass is generally climbed in the spring, when there is ample snow, using an ice axe and crampons to aid climbing, or in the later summer months, when the Hourglass is empty of snow and ice. Usually the biggest danger in the Hourglass is rockfall from above, often dislodged by other climbers. In Kevin's case, much of the snow had melted on Little Bear, causing running water to coat the Hourglass, which freezes at night, leaving a thin coat of ice on all of the rock. Even with adequate equipment and experience, thin ice accompanied by loose rock makes for quite dangerous climbing conditions. Mountains like Little Bear present dangerous challenges, even in the best of conditions. The lives of accomplished and experienced mountaineers, making no mistakes whatsoever, have been claimed by Little Bear before. With that being said, it would seem that Kevin and his climbing partner, Travis, possibly made minor errors in judgement that precipitated Kevin's death.

When reading this analysis I want to caution readers from reacting. Kevin's possible errors in judgement were quite minor, and depending on the circumstances, possibly not the worst decisions that could have been made at that time.

Choosing to climb Little Bear during the early part of June makes for a difficult and challenging climb, given the route's reputation and the challenges it presents when it is not completly full or devoid of snow. These challenges have been well-documented on 14ers.com, where Kevin frequently researched the mountains he climbed. According to 14ers.com, the Hourglass route of Little Bear is, "probably the most difficult standard 14er route." His partner, Travis, indicated that Kevin generally conducted meticulous research before climbing a mountain. 14ers.com has over 100 trip reports for Little Bear, many of them outlining the dangers that can be found on that mountain. So, going into this climb, Kevin certainly knew of the risks and dangers that could be present.

Compounding these findings is the fact that Kevin found himself in a similarly precarious situation just a year prior, where he was rescued by helicopter on the Maroon Bells, another set of very dangerous mountains. That trip report can be found HERE. During that climb, Kevin was traversing to the second peak when adverse weather conditions moved in and deposited snow on the mountain. In those accounts, Kevin stated, "Looking back, it was clear that with only a few exceptions, we made the right decisions. For one, despite the fact that my personal weather forecast/prediction said I was safe and NOAA said we were safe until afternoon, weather is unpredictable - I shouldn't have taken the chance of heading for North Maroon even though we were ahead of schedule. Second, I shouldn't have set foot on the snow to begin with."

Kevin's own analysis of those events was very mature, and it seemed that he learned a great deal from his experience on the Maroon Bells. Kevin should have learned a valuable mountaineering lesson - knowing when to turn-around and go back down. This is what makes Kevin's tragedy on Little Bear so baffling. The very lesson he learned on the Maroon Bells very well may have saved his life, or caused him to not pursue such a difficult mountain like Little Bear without more experience or better conditions.

It seems that both Kevin and Travis made the right analysis at first - in finding the Hourglass covered in ice, they decided it would not be safe to continue. Unfortunately, instead of climbing back down to a safe location, they chose to climb up onto looser terrain to wait for the ice to melt. It is easy to see how many other people could make the same decision - especially since the Hourglass is quite steep and not easy to down-climb. The idea of down-climbing was probably not as appealing as waiting on a loose ledge.

Lastly, Kevin relied on the use of a SPOT beacon during his rescue on the Maroon Bells, a device that can be used to transmit an emergency rescue message via satellite to Search and Rescue teams. The SPOT beacon requires a clean line-of-sight with the sky from all directions, something the Hourglass does not provide. The use of such equipment potentially lulls climbers into a false sense of security, giving them the idea that if they were injured, a rescue would not be difficult to obtain.

In conclusion:

- Kevin made a very good initial assessment to not continue up the Hourglass due to ice being present; however, he chose to wait on unstable terrain without adequate protection (rope, harness, anchor).

- Climbing the Hourglass in similar conditions should only be attempted with adequate protection and knowledge of its use.

- Climbing the Hourglass is recommended only when snow is completely absent or when snow completely fills the gully.

- Caution should be taken when employing the use of equipment such as a SPOT beacon. They are not adequate protection from injury and should not be used in lieu of adequate training and preparation.

- Some mountains are just plain dangerous. We will never truly know if Kevin could have done much differently to avoid his death, other than not climbing to begin with. Clearly, I don't want to advocate that no one should ever climb mountains; however, before attempting mountains like Little Bear, one should have a keen sense of their personal limitations, and trust their instincts if something does not feel safe.

A memorial fund has been created in honor of Kevin. Details of that fund can be found HERE.

3. Jeffrey R. Rosinski - Longs Peak - Keyhole Route - 7/15/2010

Jeff was a 29-year-old man from Middletown, Rhode Island and the associate pastor of the Kings Grant Fellowship Church in Portsmouth, RI. Rosinski was also a clinician at Rhode Island Hospital. Jeff was also married and was the father of two young children: a 2½ year-old boy and an eight-month-old girl. Jeff's body was found by another climber, Corbin Mabon, at 3 AM the following day, along a section of the route known as "the Trough." Based on where Jeff's body was found, it is not entirely known how he came to die; however, it would seem that he was hiking late at night (possibly in the dark), and went off-route and fell up to 300 feet from above. The terrain above the Trough is quite steep, and venturing off-route into that part of the mountain would almost certainly lead to trouble for almost anyone. If you look at the next photo of the Keyhole on Longs Peak, you can see steep cliffs to the left of the Keyhole - the rock terrain above the Trough is quite similar to those cliffs.

This particular incident was quite interesting to me, personally, because I climbed Longs Peak the day after Jeff's body was found, and saw some of the forensic evidence that still remained on the trail. According to Mabon, the winds on Longs that morning were fierce, which could have caused Jeff' to want to get off the summit quickly.

Analysis

Not much is known about the circumstances surrounding Jeff's death, or the events leading up to his fall. What I have been able to learn, through correspondence with Jeff's father-in-law, Jim Treat, is that Jeff was not an especially experienced mountaineer. He had been training on Mount Washington in New Hampshire in preparation for attempting to climb Longs Peak.Mount Washington is a respectable mountain by most's standards; however, at 6,288 ft in elevation, it is not fair to compare it to Longs Peak, which has an elevation of 14,255 ft. Additionally, the conditions and technical requirements of the two mountains are completely different. Additionally, Longs Peak is a very long and strenuous climb. It is very easy for beginner hikers to become tired, not only from the elevation that is gained, but also from the length of the hike. Due to the lack of information surrounding Jeff's death, I can only speculate that he went off-route and fell. While the Keyhole route is littered with "bulls-eyes" that show hikers where to go, it is still easy to get off-route if you are not experienced in route-finding or with Longs itself.

In conclusion:

- Longs Peak is a difficult mountain - unless you are in peak physical condition and have experience in Colorado mountaineering, it is advised that you not climb Longs Peak.

- Unfortunately, because Longs Peak is inside of a National Park, where thousands of people visit each year, it is all too often climbed by people lacking adequate experience, preparation, gear, or physical condition. Based on descriptions of Jeff, it would seem that he could have fallen into at least two of those categories.

- It seems that Jeff went off-route, even with the presence of the bulls-eye markers that show people where to go. It is important to research your route before you attempt a climb such as Longs Peak. Without a good route description or map and navigation skills, it can be quite easy to get lost or disoriented, especially if you get a late start or encounter difficult weather conditions.

4. Robert Doyle - Mount Cutler - 7/25/2010

Robert was a 19-year-old man from Colorado Springs, CO. He was killed in a fall on the southeast rock face of Mount Cutler, near Colorado Springs. Doyle was a 2009 graduate of Cheyenne Mountain High School in Colorado Springs and an avid outdoorsman. Not much is known of Robert's mountaineering experience; however, he was not aware that a trail existed up Mount Cutler, and attempted to climb a loose section of the mountain. According to Christian Crookham, the group Robert was with reached the top of Mount Cutler, but worried it would be dangerous to go down the way they came up. Crookham took the trail, while Robert and another friend took the more risky descent. According to The Gazette, the two were climbing down a rock when Robert decided to jump down to the next ledge, slipped, and fell into the canyon below.

Analysis

Not much is known about Robert's mountaineering ability or the footwear he was wearing the day he fell. What is known is that Robert climbed a relatively dangerous route on a fairly easy mountain that has an established route on it. This information paints a picture of someone that was probably just out to have fun on a sunny July afternoon, not knowing that he could get into a dangerous situation on a seemingly easy mountain. Even the easiest mountains present dangers if they are not taken seriously or if one strays off-route without the proper gear, equipment, or training. It would seem that Robert was not adequately prepared for what he encountered and placed himself in a dangerous situation. This is especially troubling considering that a much easier route existed and that others in his group heeded caution. Unfortunately, this situation is not uncommon and is described in more detail in the psychology section of my mountaineering safety article. My analysis is that Robert was the victim of psychological pitfalls.

In conclusion:

- Robert climbed a mountain without knowing anything about it beforehand. This is highly discouraged unless your equipment and experience are adequate to adjust for situations you may find yourself in.

- Robert descended a dangerous route, despite he and his group recognizing that it was not a safe route to take.

- It is possible that Robert may have viewed himself as being invincible, ignoring dangerous warnings and proceeded on a dangerous route carelessly.

Robert seems to have been a well-liked young man with a real passion for the outdoors. My condolences go out to his family and friends.

5. Peter Topp - El Diente Peak - 7/26/2010

|

|

|

Photo courtesy of Doug Hatfield, taken the day of the accident |

Peter Topp was a 59-year-old retired colonel and experienced mountaineer who perished on the jagged ridge between El Diente Peak and Mount Wilson, located in the rugged San Juan Range in southwest Colorado. According to Peter's 14ers.com profile, he had climbed 47 fourteeners, an indication that he had adequate experience for a climb such as El Diente.

According to the Colorado Springs Gazette, a party of five climbers were traversing the 1.5 mile ridge between the two mountains when the accident occurred. This particular ridge is well-known as being quite dangerous, loose, and difficult to navigate (author's note: at the time of this article's writing I have not yet completed this traverse). After leaving El Diente's summit, the group of five worked their way along the ridge towards Mount Wilson. They reached a notch on the ridge and were climbing up a steep gully to the next ridge point when a climber above dislodged some loose rock, which cascaded down, hitting three of the climbers below, including Peter. Peter was wearing a helmet, which is an excellent precaution for climbs such as this; however, the rockfall hit Peter in the head and torso, knocking him unconcious and eventually killing him. It is not known if Peter's group caused the rockfall or if another group ahead of them triggered the rocks to fall.

Analysis

El Diente Peak, and most of the mountains located in the San Juan Range for that matter, are full of loose and dangerous rock. It is well-known that the ridge between El Diente Peak and Mount Wilson is a strenuous and dangerous route that presents challenging route-finding obstacles. Not much can be said regarding precautions that Peter or his group did or did not take. He was wearing a helmet and following the correct route. For all intents and purposes, Peter did everything right. If there was anything that could be taken away from this accident, it would be some safety precautions when hiking in groups up steep sections of rock:

- Climb one at a time while the rest of the group is sheltered from rockfall, or climb along parallel paths so that if rocks were to fall they would not hit anyone.

- Pay attention to your surroundings at all times - be vigilant about who is above and below you, and take extra precautions to prevent rocks from falling.

- If rocks do fall, make sure you notify others by yelling, "ROCK!"

- Get up earlier to beat crowds - if you're ahead of the rest of the climbers, you don't need to worry about rockfall above you (but you should still be cautious about knocking rocks down on people below you).

It would seem pretty clear that Peter's death was one of those "freak accidents" that sometimes "just happen" on mountains. Unfortunately, you can't control the behavior of others that climb above or below you, so there will always be risk of rockfall unless your group sticks to a very clear plan of avoidance. When I climbed Mount Lindsey's 4th class ridge in 2008, my climbing partner and I were very concientious about rockfall danger, and made sure that we took turns ascending and descending steep sections, constantly communicating about our location and when it was safe to for the other person to continue. Even using such precaution, there will always be risk of rockfall that is not avoidable.

Peter was obviously a well-respected family-man and generally great person, as evidenced by the out-pour of grief after his death. His death was a real loss to the Colorado mountaineering community. I can only say that I am hopeful that when it is time for me to die that I am doing something I love when it happens - just like Peter.

6 & 7. Duane and Linda Buhrmester - Crestone Needle - Ellingwood Arete route - 7/27/2010

Photo courtesy of Michael Buhrmester - Vestal and Arrow Peak

Duane and Linda Buhrmester, 57 years old and 56 years old, respectively, were washed to their deaths during a very violent storm on Crestone Needle. The couple resided in Plano, Texas, where Duane was the associate dean of the School of Behavioral and Brain Sciences (BBS) and a professor of psychological sciences at UT Dallas. Linda Buhrmester ran an in-home childcare company. Both were quite accomplished climbers and mountaineers with the adequate training, expertise and equipment to tackle a difficult route such as Ellingwood Arete.

Custer County Coroner Art Nordyke provided his analysis to thedenverchannel.com:

Custer County Coroner Art Nordyke provided his analysis to thedenverchannel.com:

The Buhrmasters were ascending a near-vertical cliff when they were blasted by a torrential downpour, Nordyke said. They fell about 500 feet and then were carried about 300 feet farther by a mudslide that buried their bodies. "It was very violent," he said. "It looks like a huge amount of water came down that washed them off the mountain." "The mudslide buried them. We're just lucky we found them," Nordyke said.

It is not known if they were roped up and using anchors when the accident occurred; however, they did have climbing rope with them. It is also highly probable that even if they were roped up and using anchors that the severe storm could have taken them off of the mountain anyways.

Not much else is known about the accident that led to their deaths; however, through the gathering of evidence and through knowledge about his parent's behavior patterns, Michael Buhrmester provided some insightful thoughts about the timeline of his parent's death on a message board thread on 14ers.com:

Mom and dad walked in from the trailhead to Upper Colony Lake on Monday the 26th in the mid afternoon. They camped there for the night. They would have gotten up well before dawn, knowing that weather could be an issue (they had actually gone into last labor day to climb Ellingwood but there was so much rain they never attempted the summit climb). We found only one eaten dinner in their tent and several more days worth of food, suggesting they attempted the summit climb on Tuesday the 27th. They likely saw that the weather was changing for the worse at some point on the Ellingwood route (unsure when, but it is fairly certain they did not summit because they would have descended the standard route, but that's not where they were found, they had also not eaten their packed lunch, which we normally do on the summit). Upon seeing the weather changing, they would have tried to get down as safely and quickly as possible. Its likely they rappeled or down-climbed to the gully/chute to the north? (right of the route if you're looking at the regular face pictures of the route) where it probably looked safest and most direct to the camp. At some point during their descent, there may have been a major rock/mud fall hitting them and carrying them perhaps several hundred feet. I believe this is what happened because mom and dad weren't roped together when found (mom had a mountaineer's coil over her shoulder and had both ends of the rope, suggesting they had used the rope earlier and had it at the ready should they need it again). If they were in that chute with much scree, they knew that it would have been safest for them to not be tied together because of the potential for the rope to get caught on loose rock and cause rockfall. Both were also wearing their boots when found, and had their rock shoes in their packs, suggesting that they had not taken a fall on a technical pitch where they would have been wearing their rock shoes. I suspect they got pretty high up the arete in their rock shoes, bailed, switched to boots as they probably didn't want to twist an ankle in their rock shoes on any loose scree, then encountered a rock slide. Based on where they were found and the likely weather issues, we think this is what happened.

Analysis

Based on the thoughtful analysis provided by Michael above, it is difficult to speculate if anything could have been done differently by Duane and Linda to prevent their deaths. Severe weather is always a risk when climbing mountains in Colorado; even on the clearest of days with the best forecast, lightning and rain and move in quickly to unsuspecting climbers. This risk is amplified when climbing because of the limited range of visibility and the fact that the mountain can obscure incoming storms from view. As Michael suggests, Duane and Linda both knew of these risks and most likely began their climb as early as possible to avoid storms. The storm that killed them has been described by many locals as a freakish "100-year" event. The mudslides in the area were significant, and the aftermath can still be seen in the drainage beneath Crestone Needle, with mud and rock being deposited where none previously existed.

This accident can be categorized under the "freak accident" category. Based on an article written by Duane's former employer, UT Dallas, Duane and Linda were clearly outstanding individuals that cared deeply about those in their community. They will be missed by families and friends alike, no doubt.

Those wishing to make an acknowledgement of the Buhrmesters may send a donation to:

Buhrmester Student Development Fund

The University of Texas at Dallas

Office of Development and Alumni Relations

800 W. Campbell Road

Richardson, TX 75080

8. Spencer James Nelson - Maroon Bells - Bells Traverse - Bell Cord Couloir - 8/14/2010

Photo courtsey of Sara Hjertman

Spencer James Nelson was a 20-year-old college student from Winter Park, CO. He was a graduate of Middle Park High School and an avid outdoor enthusiast, including skiing and mountaineering. According to Skihidailynews.com:

At age 7, Spencer began racing with the Winter Park Competition Center and eventually made the ski team at the University of Colorado in Boulder. Only four months before the start of pre-season training, Spencer encountered a major setback when he was severely injured in a dirt bike accident. He broke his back and ruptured his spleen, among other things. Yet, he recovered from those injuries in time for the season and went on to become one of the team's top skiers — as a walk-on freshman.

His coach remarked to the family this week that given his dirt bike injuries, Spencer likely had one of the best seasons in history for a freshman and established himself as one of the best giant slalom racers on the team. His seventh place finish at the Rocky Mountain Intercollegiate Ski Association Championships helped the Buffs qualify a full 12-member team for the NCAA Championships.

Nelson finished his freshman season with nine Top 20 performances and finished 21st in the giant slalom and 23rd in the slalom at NCAAs, helping the team to a second-place finish.

He received the Lucie Hanusova Memorial Award, which is given to those who overcome adversity and challenges with smiles and enthusiasm.

After the season, he was honored by Colorado Ski Country USA in its Double Diamond Awards as male all-star athlete of the year.

Spencer, like many Colorado mountaineers, was determined to climb all of the state's 14ers and had already ascended 17 of them at the time of his death. The Maroon Bells, where Spencer died, is home of some of the most treacherous, loose rock of any mountains in Colorado.

Spencer summited the first of the two mountains with his group of 8, which included his father, Peter Nelson, and Mike Cronin, who is a member of the Grand County Search and Rescue team. While traversing what is known as one of Colorado's "Four Great Traverses," between North Maroon Peak and Maroon Peak, a rock was dislodged from above, which struck Spencer, knocking him 600 feet down the Bell Cord Couloir. Spencer was wearing a climbing helmet at the time of the incident. It was believed that a member of Spencer's climbing party knocked the rock loose that knocked him down.

Analysis

Based on the information that is available at the time of this report, it seems fairly clear that Spencer's death could not be attributed to anything he did or did not do, rather, similar to Peter Topp's accident above, Spencer was a victim of pure coincidence and accidental rock fall triggered by another person. It is not known if Spencer had adequate training or experience to be attempting the Bell's Traverse; however, at least one member of his party, his father, seemed to have the necessary training and equipment for the technical climb.

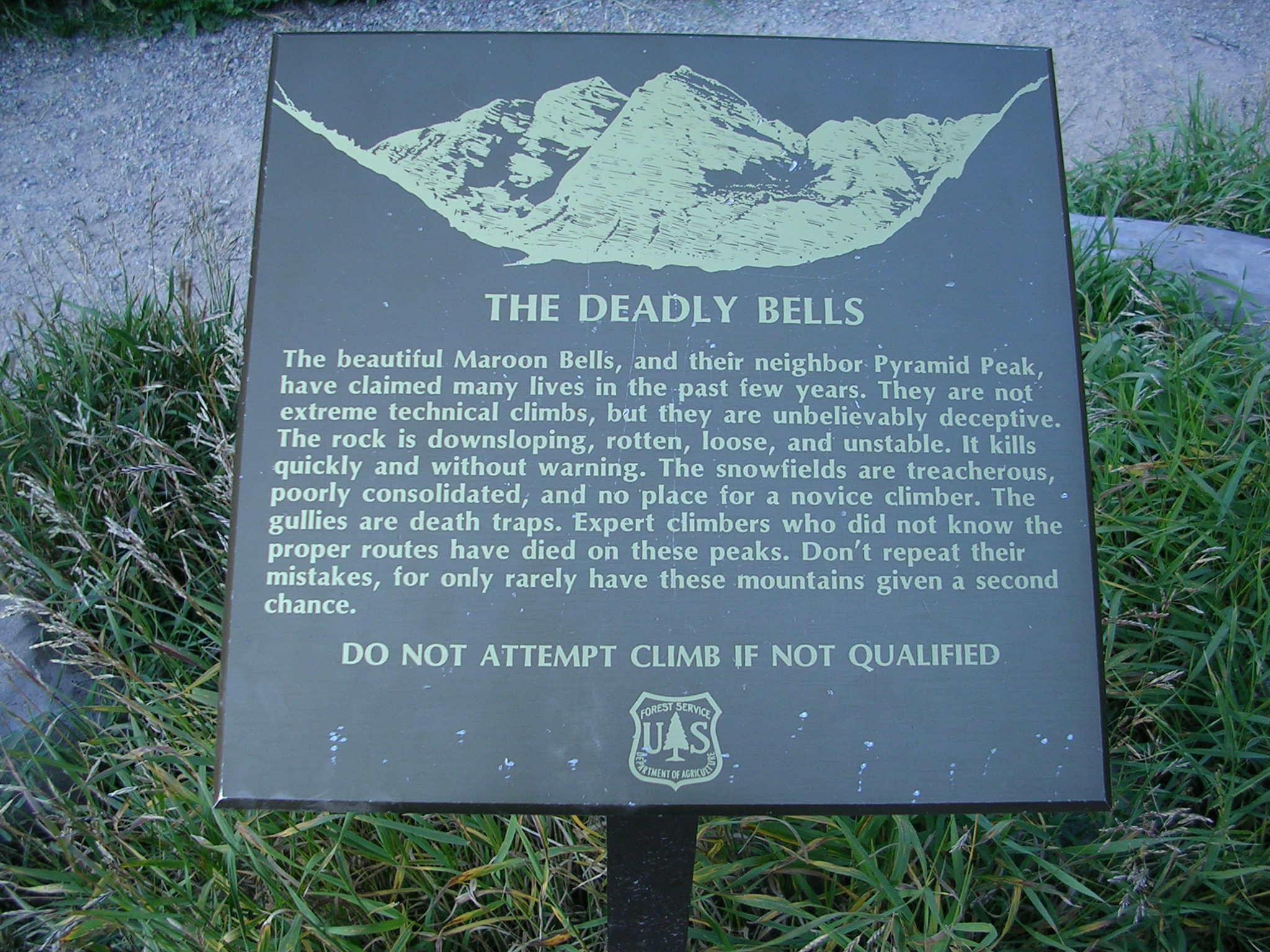

The Maroon Bells are some of the most deadly mountains in Colorado. It is not known how many people have perished on them over the years; however, a sign clearly warns hikers at the trailhead:

It would seem that Spencer's death could have been avoided if his group practiced safety precautions that should be employed when climbing in groups on steep terrain. This information is copied from Peter Topp's analysis above, but I believe it is worth repeating due to the value of the information:

- Climb one at a time while the rest of the group is sheltered from rockfall, or climb along parallel paths so that if rocks were to fall they would not hit anyone.

- Pay attention to your surroundings at all times - be vigilant about who is above and below you, and take extra precautions to prevent rocks from falling.

- If rocks do fall, make sure you notify others by yelling, "ROCK!"

- Get up earlier to beat crowds - if you're ahead of the rest of the climbers, you don't need to worry about rockfall above you (but you should still be cautious about knocking rocks down on people below you).

Failure to follow these precautions is something I've been seeing a lot lately, especially on popular 14ers. When I climbed Capitol Peak last year, I was down-climbing towards the knife edge when a group of three climbers, without helmets, came right below me and proceeded to climb up towards me, oblivious to the fact that I was above them on very loose terrain. I even warned them that I was on loose rock and that they should wait for me to continue, but they ignored my plea of caution. On Longs Peak last year, I witnessed the same thing, just after the "Narrows" section just after passing over to the "Trough." Several climbers, oblivious to the fact that many people were below them, carelessly knocked rocks down on people below, some large enough to cause significant injury or death.

It cannot be stressed enough that climbers be vigilant of the terrain they are on. Unfortunately, due to the growing popularity of the sport of climbing 14ers in Colorado, the number of people on any given mountain can be very high, making it almost impossible to mitigate the risk of rockfall caused by others. It is therefore the responsibility of each and every climber to practice sound safety precautions. In the example of my encounter on Capitol Peak, I stopped climbing until the three other climbers reached a safe distance away from any possible rockfall beneath me.

It is obvious that Spencer was a special person and well-liked by many. This is evidenced by a quote from a Facebook group created in his memory: "This is a toast to the life of a boy who had such a big heart. Today we lost someone who had so much determination and will power to be the best he could be. Someone with a world of friends and no enemies." My condolences go out to his family and friends.

9. Benjamin Russell Hebb - Longs Peak - Diamond - Dunn-Westbay route - Broadway ledge - 8/27/2010

|

|

| Photo courtesy of Jason Kaplan |

Benjamin was a 26-year-old from Broomfield, CO. He was set to graduate from the University of Colorado at Boulder in December with a degree in chemical engineering and had previously earned a degree in physics. He also worked as a research assistant at Gill Lab at CU - Boulder. Benjaimin was an expert rock climber, having spent most weekends climbing. At the time of his death, he was wearing a helmet and had all of the appropriate rock climbing gear and equipment with him for a successful ascent. Benjamin was solo-aiding the route, which involves fixing the rope to an anchor and connecting yourself to the free end with either knots or one of the various modern devices designed for roped soloing. Then the pitch is led as a standard aid pitch would be led. According to Rocky Mountain Park officials that witnessed his fall, he was unroped at the time - a common situation for experienced climbers in that location. Benjamin fell approximately 800 feet down a chimney.

Longs Peak's "Diamond" - Photo by Matt Payne

Analysis

While Benjamin was climbing solo, which is generally considered more dangerous than climbing with a partner, it was most likely not a contributing factor to his death. The section of the route he fell from is often not protected because of the comparatively easy terrain it is on. With that being said, it would seem prudent to protect that section of the route if high winds are present or if your climbing abilities are not honed (Benjamin was a very experienced climber). Placing protection on this section of the route might be more feasible if a partner is with you; however, since I have not been on the route personally, I cannot attest to that. It would seem that Benjamin fell on one of the "easier" sections of the route, while unprotected - a relatively common event for expert climbers. The easier sections of any given route are often free-soloed due to the speed by which a route can be accomplished. Obviously, even on easier sections of a route, the most experienced of climbers can still have an accidental fall, just as in the case of Benjamin Hebb. In conclusion:

- When possible, climb with others - climbing solo is generally less safe than with other people.

- When free-soloing an easy section of a route, extra caution should be employed to avoid a fall.

It is not known if Benjamin could have done anything to prevent his death, except to use protection on an easy section (which is generally not something most climbers do). This accident merely accentuates the fact that even the best climbers can still fall to their death on easy routes or easier sections of a route (which is probably one of the reasons why people climb to begin with - the rush of climbing is a powerful experience).

10. Don Thurman - Kit Carson Mountain - 9/18/2010

Don Thurman - photo courtesy of Don's hiking partner.

Don Thurman was a 63-year-old man from Parker, CO. Don perished on Kit Carson Mountain near what is commonly referred to as the "Kit Carson Avenue," a small cut-out in the mountain that allows climbers to gain access to the summit. It is not known what exactly happened to cause Don's death; however, his climbing partner strongly believes that Don fell on steep terrain after the two of them became separated after mis-calculating their exit into the Kit Carson Avenue upon descent. According to his 14ers.com profile, he had previously climbed 51 of Colorado's 14ers. Don went by the name of PeakCowboy on 14ers.com and was known by that community as one of the nicest and most pleasant individuals on the site, as evidenced by some of these comments about him:

- "I was deeply saddened to hear of Don's passing. I only had the honor of climbing with Don once, but it was one of the most memorable climbs I have had."

- "Don Thurman possessed a powerful drive and desire to experience the outdoors. He was an accomplished outdoors-man, and was always ready for the next challenge. I had the great pleasure of making Don's acquaintance via 14ers.com."

- "He's a great guy, very experienced, knowledgeable, and fun to talk with. I had never done a bear bag before and he showed me how to do it correctly."

- "He was a great companion and a careful climber. Each outing [with him] is a cherished memory."

Analysis

Don was clearly an experienced and accomplished mountaineer - he had been climbing mountains for several decades. His skill level was certainly high enough to tackle Kit Carson's relatively difficult terrain. Although Don had an undisclosed medical condition, it is not believed that it was a contributing factor in his death. Both he and his climbing partner were wearing helmets at the time of the accident. It would appear that what happened in this case was that Don and his climbing partner "missed" the exit to the Kit Carson Avenue while descending from Kit Carson's summit. When the Avenue is "missed" in this fashion, climbers descend too far into much steeper, looser terrain which requires careful climbing and route-finding to escape. This is a relatively common mistake on Kit Carson - in fact, my climbing partner, Terry Mathews, made the same mistake when we climbed it together in 2009. Fortunately, he was able to reverse course and ascend out via the Avenue properly. The Kit Carson Avenue can be seen in the below photographs. The first, a view of the Kit Carson Avenue as seen from Crestone Peak - photo courtesy of Terry Mathews. You can see that the terrain below the Avenue is quite steep.

To get a sense of just how steep and dangerous the terrain becomes once one misses the Avenue, take a look at the next photograph that I took in 2009:

Based on what is known about Don's death, it is not certain that he could have done much differently to avoid his death. He was wearing the proper equipment, he had the necessary skills and experience, and he was hiking with a competent partner. If anything could be learned from his accident, it would be:

- When climbing, one should take careful notice of their surroundings, making special mental notes of geographical features when changing directions or climbing up from another feature.

- By taking these mental notes, you will help remember where you need to go upon descent to prevent finding yourself off-route in much more dangerous terrain.

- By reading other's trip reports one can read about different pitfalls and things to look out for on a given mountain. This is not the first time I've heard of someone "missing" the Kit Carson Avenue, and I am certain it won't be the last.

- If you are planning on climbing Kit Carson, make sure you pay attention when you are leaving the Avenue to finish the climb. Look for unique rocks, cairns, or other unique features to clue you upon your descent.

11. John Regan - Longs Peak - Keyhole route - 9/25/2010

John Regan, a 57-year-old from Wichita, Kansas, died after falling about 300 feet from "The Ledges" on the Keyhole Route of Longs Peak. In response to this fatality, Rocky Mountain National Park changed the rating of the route to technical. The fall happened on the where two metal bars protrude from the rocks on the trail. See below:

Not much is known about John or the accident other than the fact that he slipped off of the mountain on a narrow section.

Analysis

John's accident was one of many on Longs Peak in 2010. Not much is known about John or his climbing capabilities, mountaineering experience or equipment. John's death reads quite similar as Jeffrey Rosinski's - an inexperienced climber who underestimated the mountain's difficulty. That is most likely the number one issue with Longs Peak, in general. Due to being in a National Park, Longs attracts thousands of visitors per year, many of which have little to no experience with climbing mountains. It is also possible that the section of the route that John fell from was iced-over and slippery.

In conclusion:

- Do not attempt Longs Peak unless you are an experienced mountaineer in excellent physical condition or unless you are with an experienced individual.

- Take extra caution on "The Ledges" section - it is slippery even on the driest of days due to the rock being worn down by years of boot traffic. Mountaineering boots such as the La Sportiva Trango or ascent shoes, not tennis shoes, should be employed to climb mountains such as Longs Peak. Excellent footwear is vital for grip, support, warmth and protection.

12. John Merrill - El Diente Peak - 9/26/2010

John Merrill was a 30-year-old climber from Cortez, CO. John was crushed by rockfall in nearly the same location as Peter Topp, exactly two months later. He was hiking alone with his dog, Oof. El Diente Peak would have been his fifteenth 14er. John was survived by his pregnant wife. John's dog, Oof, was rescued by a Search and Rescue operation the following day. The dog is now being cared for by Kacey Long, according to Watchnewspapers.com.

In searching for information about John Merrill, I stumbled upon his best friend's blog, which portrays John as being a lover of the outdoors and of elevated summits. In this blog, his friend, Tom Alphin writes about John:

"John has always been obsessed with reaching high places professionally and personally. I have always found the biggest reward for reaching high places were the clear views around me, but I think for John, part of the reward was the ability to see himself more clearly."

Analysis

Since John was by himself when he died, not much is known about what caused his death other than the evidence left behind by the rock fall that he died from. All signs point to this being a freak accident, almost identical in nature to the circumstances surrounding Peter Topp's death. It is not known if John was wearing a helmet or if he died instantly from his wounds. It is also not known if John's dog, Oof, played any role in the rockfall. What is known is that John's mountaineering experience was likely limited, based solely on the number of summits he had completed. The only mistake John likely made was climbing such a difficult mountain by himself without prior experience on similarly difficult terrain. In conclusion:

- Generally speaking, it is not a good idea to climb mountains by yourself unless you have significant mountaineering experience and / or a SPOT beacon.

- Climb within your abilities. There's no shame in turning around if a mountain presents challenges that you do not feel comfortable with.

- Test your footholds and handholds before placing a significant amount of your weight on them. This is especially vital in rugged terrain like the San Juan Mountains or Elk Mountains of Colorado.

- Climbing mountains with dogs is a personal decision. On more difficult terrain found on mountains like El Diente Peak, it is generally not a good idea to bring a dog with you since dogs tend not to be careful about rockfall, etc.

- Read above examples on how to climb safely on steep terrain to avoid rock-fall.

13. James Nelson - Mount of the Holy Cross - 10/3/2010

James Nelson is a 31-year-old man from Chicago, IL. No one has seen him since he went missing on October 3rd, 2010 when he set out for a five-day, 25 mile hike in the Holy Cross Wilderness Area. At the time of this article, James is presumed to be deceased; however, his body has yet to be found. Several attemps have been made to locate James to no avail. The circumstances leading up to, and following his dissappearance are murky, convoluded and controversial, as evidenced by the discussion on 14ers.com. Some speculate that James attempted Mount of the Holy Cross and fell - James had shared his proposed route with some friends before leaving Chicago and in those plans was a tentative scheduled climb of Mount of the Holy Cross. Others believe he became lost, similar to the case of Michelle Vanek, who famously went missing in the Holy Cross Wilderness Area in 2005. Some people speculate that he was killed and consumed by a mountain lion, despite a lack of evidence available to support that theory. It is also quite possible that James, being alone, became injured - perhaps a twisted ankle or knee ligament tear - and was far enough off the beaten path that no one could find him to rescue him. Clearly, not much is known about what happened to Mr. Nelson, and we probably will never know. What we do know is that he was somewhat experienced in backpacking, having led several trips with his Chicago Backpackers Meetup Group since 2006. Also, James was well-equipped with the proper gear and supplies for a long backpack trip.

Update: 5/27/2012: It would seem that the remains of James was finally found in the Holy Cross Wilderness Area: http://www.denverpost.com/commented/ci_20720181?source=commented-

Analysis

Embarking on a 5-day, 25 mile backpacking trip in a wilderness area notorious for lost hikers is a challenging undertaking for almost anyone. It is not known if James had the necessary fitness level or experience to accomplish such a feat. One of the last people to see James stated that he "covered the same ground it took James 45 minutes to cover in 10 minutes." This would seem to indicate that James was having trouble carrying his heavy pack at high elevation. A logical possibility is that James became exhausted from Acute Mountain Sickness at some point (read more about the impacts of AMS HERE). This could have led to any number of fatal mistakes, including straying off-route, falling down dangerous terrain, or other physical disabilities that could have impacted his ability to complete the hike safely. With that being said, it is also entirely possible that James was in great shape and that some other tragic event took place to explain for his disappearance.

Unfortunately, James' case presents us with several opportunities to learn some key lessons about wilderness travel:

- Make sure you are in good enough shape to accomplish the goal at hand - climbing mountains and backpacking are very physically demanding activities.

- Know the area you are traveling into before leaving home. While James had a GPS with him, he was traveling into a very wild part of the backcountry. Without first-hand knowledge of the area, James took some risks by traveling there by himself.

- If possible, hike with others - this ensures that if you are injured that someone can get help to rescue you.

14. James Patrick - Taylor Peak and Powell Peak - Rocky Mountain National Park - 10/16/2010

James Patrick was a 54-year-old licensed master plumber from Littleton, CO. He fell 1,000 feet down Taylor Glacier on steep terrain. During his fall, he pulled down his group's climbing rope, which stranded the other two climbers that were with him whom were later rescued. I have not been able to find many other details about James or the accident which caused him to perish. Apparently, his accident occurred during a sponsored trip from the Colorado Mountain Club, so many of the details of the accident are kept secret for legal reasons.

Analysis

Unfortunately, not much else is known about the accident. Based on the research I've done, it would seem that the cause of the accident was technically-related, meaning, either some piece of climbing equipment failed, or James made a mistake with his climbing equipment (knot / protection placement / etc).

15. Chris Pruchnic - Thatchtop Mountain - 11/20/2010

Photo courtesy of Kiefer Thomas

Chris Pruchnic was a 42-year-old man from Denver, CO and the former chair of the Front Range Section of the American Alpine Club. Chris was a very experienced mountaineer and ice climber. Chris was attempting an ice climbing route known as "All Mixed Up," located 1,200 feet above Mills Lake in Rocky Mountain National Park. Chris was climbing with one other person at the time, who was not injured. The route is very steep with loose ice and talus. It is one of the most famous ice climbing routes in Colorado. Chris was one of the most well-respected climbers in the Denver area, as evidenced by comments left by other climbers and people that knew him:

- "Even though I knew only a few morsels of his life, I will remember his kindness, his refreshing perspective on life and living it to the fullest, that went hand in hand with his passion for the outdoors from the deepest depths to the highest heights."

- "You'll be greatly missed as a climbing partner, a mentor, and most of all a great friend."

- "He had an infectious love of the outdoors and truly loved to give back. He will be greatly missed, in many ways in the climbing community."

Analysis

Not much is known about the details of the accident that caused Chris to fall to his death. It could have been ice conditions, gear malfunction, technical oversight - or a combination of all three. The route that Chris fell from is highly technical and quite difficult, even for experienced mountaineers. The very nature of ice climbing includes risks that are generally accepted as part of the sport. Placement of protection is generally difficult, and even more so on routes such as All Mixed Up. It is quite possible that Chris placed an ice screw or other form of protection, fell, and the protection failed. This is actually fairly common in ice climbing because of the way in which the protection is placed into the ice. According to an article on ezinearticles.com by Phil Lyall:

"Putting a piece of protection into ice is not easy. Most commonly you are looking at putting in an ice screw, which is very similar to a normal screw but larger: about the size of a plastic tent peg. There are no pre-bored holes in ice, so one must first chip a small area of ice away for purchase: a depression that allows the screw to bite. If you are lucky the screw does bite and then you are able to begin boring into the ice. No screw drivers, no vises, no warm basement workshops, and no hands because you are still clinging by ice axes to the approximately perpendicular face of waterfall ice. Houdini would have appreciated the act. Placing a screw is difficult. Placing a screw in the throes of worrying about a fear-fall, is next to impossible."

In conclusion:

- Ice climbing is dangerous, even for experienced mountaineers. Take extra caution when engaging in this sport.

- Route conditions can negatively impact your ability to safely complete a climb. Before starting a climb, evaluate the conditions of the route and make a sound decision on whether or not to continue.

- Check your equipment before starting a climb - make sure your rope is in good condition. Stewart Green from about.com provides good advice on how to do this.

Summary / Data / Charts / Common Themes

2010 marked one of the deadliest mountaineering years in history for Colorado. As an avid hiker and mountain climber, I could not help but take special notice of each death, as each incident personally impacted me due to the fact that these people died doing something that I do almost every weekend. Witnessing the impact of these deaths on the hiking community at large, and reading the misinformed reactions of non-participants of the sport inspired me to research each death and try to formulate explanations for the lay person, the expert and everyone in between. I realize that this is a quite controversial undertaking, and also know that there will be critics. To reiterate from my introduction, I believe that this is an acceptable risk for me to take if even one person reads this article and learns something from it.

Many have speculated that the up-tick in deaths is caused by an increase in climbers and new hikers to the sport of hiking and climbing mountains in Colorado. I have a different set of explanations that I'd like the reader to consider:

- The digital era has made it even easier for people to access information, whether that be news or information about the sport in general. As media outlets continue to saturate the market with news of events via print, websites and social media, the public's awareness of deaths and accidents will increase.

- So too will the public's access to information on how to climb mountains - in fact - many people believe that sites like this one and 14ers.com have only made things worse by encouraging people to climb when they are probably not physically or mentally capable of it.

- In reviewing the statistical tables of mountaineering deaths in North America, I've discovered, at least on a surface-level, that there is not a meaningful or significant increase in the number of accidents over the past 50 years. This would seem to debunk the theory that because more people are climbing mountains, more people are dying.

- The increase in 2010 is therefore most likely only a fluke.

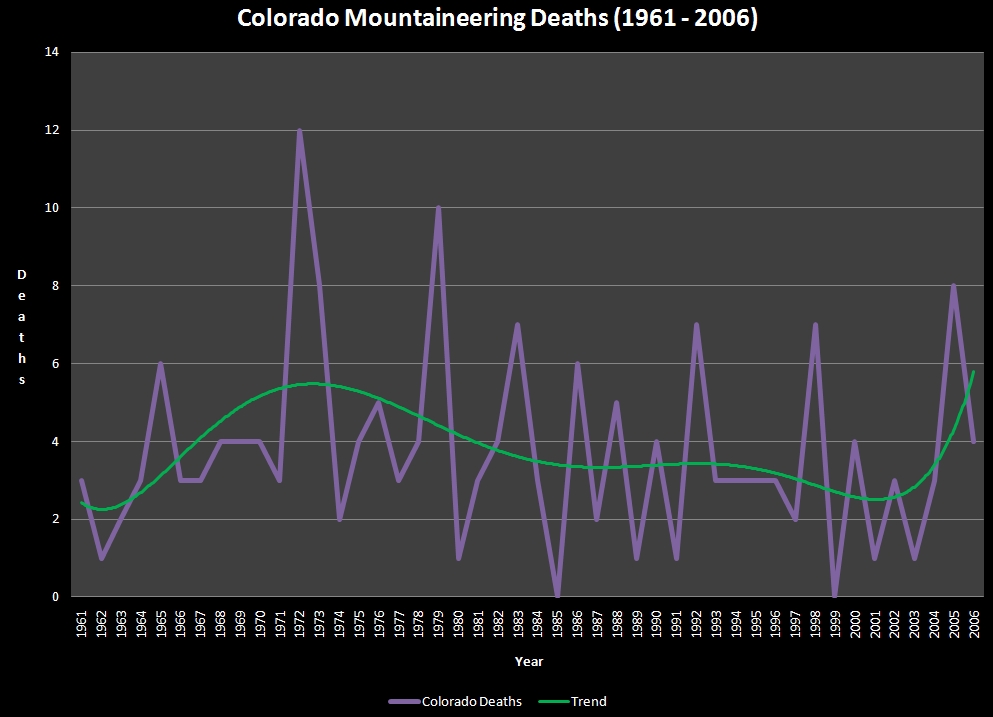

The below charts were created using data from the ANAM statistical tables. Chart 1 shows Colorado Mountaineering Deaths from 1961-2006. While ANAM captures all death types (avalanches, rock climbing, etc) and does not drill down to show Colorado-specific data for mountain climbing, it is still good data to analyze. As you can see, the trend has remained relatively static over the past 50 years, with only a slight increase in the past decade. ANAM has not released 2007-2010 data at the time this article was written.

Chart 1:

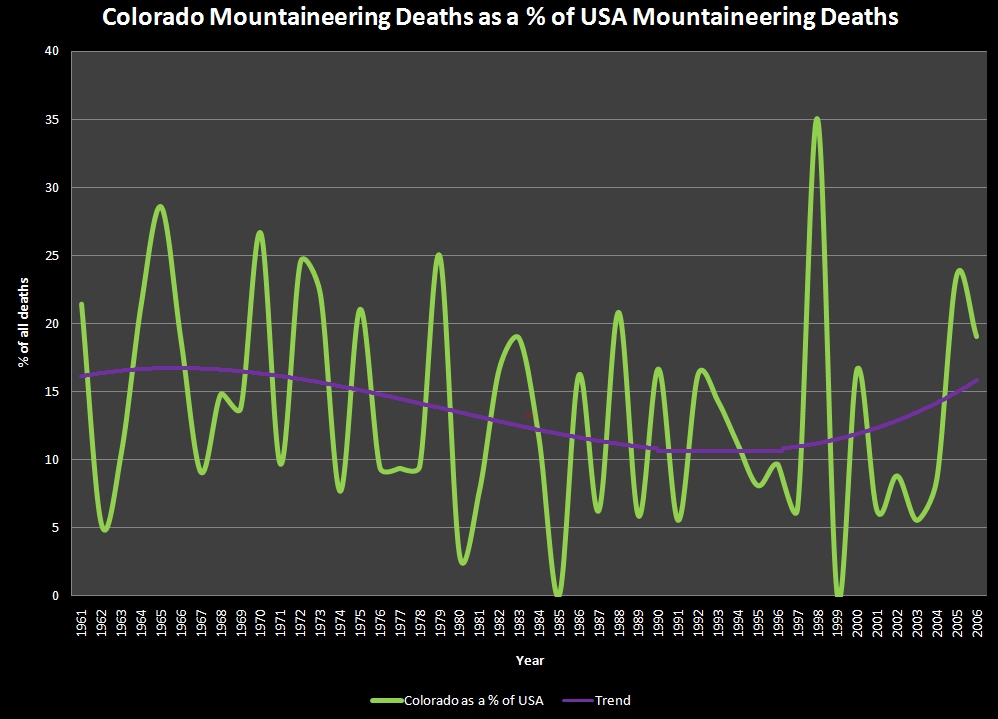

Chart 2 illustrates Colorado mountaineering deaths as a % of USA mountaineering deaths. This data is useful because it shows that Colorado is not an outlier for mountaineering deaths.

Chart 2:

Again we see that the trend is that deaths have been relatively static with only a slight up-tick in recent years.

There were some common themes of the deaths this year:

- Highly experienced mountaineers perished on difficult mountains or routes. This is not surprising if one considers that as one becomes more experienced, they will pursue more difficult mountains or climbs. Compound this with a steady increase in self-confidence, which may deter a climber from taking precautions they normally would, and there is increased potential for risk and subsequent death.

- Inexperienced mountaineers perished trying to climb mountains that probably exceeded their ability, expertise or equipment.

- 6 out of 15 (40%) deaths were individuals over the age of 50.

- 3 out of 15 (20%) deaths were individuals 20 years or younger.

- Longs Peak was the most deadly mountain, followed by El Diente Peak and Crestone Needle. All three mountains require "Class 3" climbing or harder.

- The quest to summit all of the 14ers seems to drive people to attempt mountains that are either beyond their skill level or during poor conditions.

- Some of the victims were almost finished with their quest to summit all the 14ers. The increasing use of these lists to establish mountaineering goals (of which I am guilty of as well) may not be practical for all climbers, especially when their final climbs are considered to be highly dangerous (Thanks to Curt Kennedy for pointing this out to me).

- Longs Peak is dangerous. Tourists, beginners and inexperienced climbers beware!

If you are considering climbing mountains in Colorado and found the contents of this article overwhelming, consider joining the Colorado Mountain Club and taking their Basic Mountaineering class. At the very least, please take the time to read the contents of my mountaineering safety article. Be safe out there!

Longs Peak and Mount Meeker via "The Loft"

I have to admit, when I put together my climbing schedule for this summer, one of the mountains I was least looking forward to climbing was Longs Peak. Renowned for a very long approach and a trail full of people, Longs Peak is the closest 14er to Denver, Ft. Collins, Greeley and Boulder. Longs can be seen from the I-25 corridor running from south Denver, all the way north to the Wyoming border. It is an impressive and memorable looking mountain, with it's east face holding one of the most popular and famous alpine climbing routes, The Diamond.

To start off, here is a break-down of relevant numbers from this memorable trip:

Peaks summited:

Longs Peak: 14,255 ft. (ranked 15th in Colorado)

Mount Meeker: 13,911 ft. (ranked 68th in Colorado)

Total elevation gain: 6,385 ft.

Total distance hiked: 16.52 miles

Total time hiking: Approx. 12.5 hours

Total wildlife sightings: 1 (Elk Herd)

The Diamond.

For this particular trip, I invited my dad, Ray Payne, to join me. He had climbed Longs before, but had previously missed out on summiting Mount Meeker, one of Colorado's highest 100 summits. Ray was eager to join me so we made plans to stay the night in a small hotel near the trail-head for Friday night. Our reservations were made months in advance by my mom, since she knew the area was quite popular (thanks mom). Ray and I chose "The Loft" route since it is less popular and more challenging than the standard "Keyhole" route, and because it grants instant access to Mount Meeker. This turned out to be a great choice.

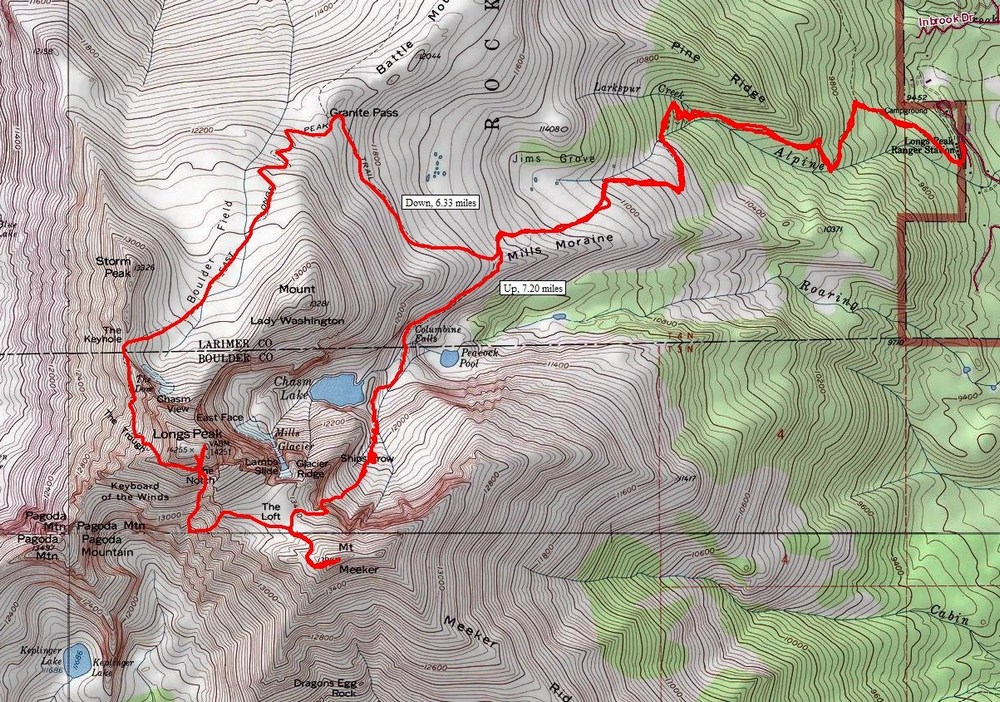

A topographical map showing our route

Ray and I drove to the Meeker Park Lodge from Colorado Springs after work on Friday evening. Ray and I set our alarm for 2:00 AM and went to bed as early as we could. The Lodge itself is a quaint, rather rustic building with a "touristy" feel. The room itself was pretty basic and lacked many amenities; however, this was perfect for our needs. We needed a bed close to the trailhead. Mission accomplished.

The alarm went off all too early at 2 AM and we quickly woke up and ate some quick breakfast. We departed for the trailhead, a mere 3 minute drive from the Lodge. We began hiking at 3:11 AM. The parking lot was completely full already, much to my surprise. There were many groups assembled, preparing for the hike up Longs. I was not very happy about the amount of people; however, this turned out to not matter much shortly into the hike.