This article highlights various concepts relating to mountaineering safety in Colorado.

Table of Contents

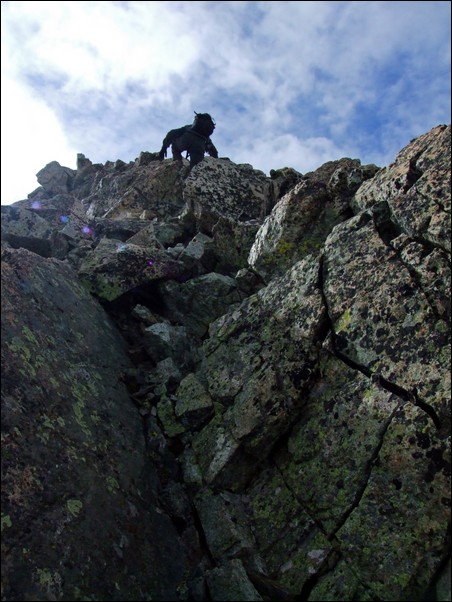

Photo by Terry Matthews (RIP) - Matt Payne wielding an ice axe to safely get down from Crestone Peak

If you're reading this article, chances are you are a climbing or hiking enthusiast that just flat-out loves the Colorado mountains. If you're like me, you were hooked the first time you reached the summit of a mountain, and each time you reach the top of a new one, the urge to conquer another mountain and experience all the great feelings that go with climbing grows even stronger. We start to set goals for ourselves. Typically, we start by stating we are going to climb all the 14'ers, then the top 100 mountains in Colorado... and before you know it, you are making plans to climb Denali! Unfortunately, we all have to start somewhere, and most of us were not born with all of the knowledge required to climb mountains safely. With over 500,000 people attempting to climb a 14'er in Colorado each year1, the odds of accidents, fatalities, and close-calls has increased steadily over the past decade. Despite the growing popularity of this activity, the fact remains that mountaineering in Colorado can be extremely dangerous - in fact - many people have indeed died attempting to climb mountains in Colorado. Several factors contribute to this fact, including ill-preparation, poor judgement, psychological factors and nasty weather. The purpose of this article is to provide the reader with as much information as possible so that readers can reach the summits safely, again and again. It is important to note that this article cannot ever and will never be an exhaustive documentation of every possible safety precaution. I hold no responsibility for your actions while climbing.

I'm a numbers kind of guy - numbers paint a picture for me. And when it comes to mountaineering fatalities, the numbers are pretty clear - mountaineering in Colorado is dangerous. Sure, most of the time, people are able to get up and down safely, without incident. However, without the proper precautions, mountaineering can be fatal.

According to Accidents in North American Mountaineering2 by The American Alpine Club, mountaineering accidents and fatalities are steadily rising in Colorado. Due to a sharp increase in the popularity of mountain climbing since the 1950s, more and more people are climbing mountains, many of whom are unprepared and new to the activity. In fact, this book shows that there have been over 700 fatalities in Colorado alone during the past 40 years. In Mark Scott-Nash's book, Colorado 14er Disasters - Victim of the Game, many of these fatalities are discussed.

Additionally, according to the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment3, climbing and hiking are the most fatal recreational activities in Colorado, with 37 fatalities between 1996 and 1998; this only accounts for falling deaths and the actual number for all types of deaths is much higher.

Fortunately, death is preventable if climbers and hikers gain an understanding of the causes of death and learn to take precautions and make decisions that help to prevent death from occurring.

Matt Payne on top of Crestone Needle - with helmet securely attached!

The possible causes of death for mountaineers are numerous; however, we're going to focus on the most common ones:

1. Hypothermia: Surprisingly enough, hypothermia is one of the most common causes of death for mountaineers. This is very preventable with good preparation and suitable gear. If you can stay dry and stay warm, you will survive. Long gone are the days in which hiking with a cotton t-shirt and jean shorts is acceptable attire. Quite simply, cotton kills. It does not dry out very quickly and it does not repel moisture. Get some synthetic clothing and make sure your hiking boots are waterproofed with Nikwax or lined with Gore-Tex. Backcountry.com sells everything you would need to survive. Gear alone won't prevent death, however.

2. Falling: Many deaths in mountaineering occur due to falls. While this is most common on steeper mountains, such as Little Bear Peak, Maroon Peak, or Capitol Peak, serious injuries are fairly common even on the most seemingly easy 14'ers. Oftentimes, inexperienced climbers will stray from established routes, or underestimate the difficulty of a climb. When this happens, the likelihood of an accident increases. Additionally, many injuries and accidents occur as the result of fatigue. Even the most experienced climbers can become weary at high elevation, and by the end of the day, muscles weaken and concentration can fade. Oftentimes, fatalities and serious injuries occur during these states of physical and mental weakness, further strengthening the need for caution and self-awareness.

3. Acute Mountain Sickness: Acute Mountain Sickness or AMS occurs when people ascend to higher elevations at a rapid pace and are not acclimated to that elevation. According to Medline Plus4, Acute Mountain Sickness is "brought on by the combination of reduced air pressure and lower oxygen concentration that occur at high altitudes. Symptoms can range from mild to life-threatening, and can affect the nervous system, lungs, muscles, and heart." I've personally experienced mild AMS on many occasions at high altitude. Symptoms include nausea, difficult breathing, tachycardia (rapid heatbeat), and exhaustion. If gone untreated (if you stay at high altitude for long periods of time while experiencing symptoms), AMS can develop into coma, High Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE), and High Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE).

AMS can affilict even the most experienced climbers and hikers; however, the ailment is highly preventable. To prevent AMS, drink copious amounts of H20, get plenty of sleep and try to acclimate yourself to higher altitude as best as you can. It is generally recommended that you acclimate yourself at least one day for every 1,000 feet of elevation gain. Obviously this is not realistic for many climbers not from Colorado, so the best thing you can do is extend your stay as long as possible and gradually increase the amount of elevation you expose yourself to over time. For more on alittude acclimation, see this great article.

4. Weather: Predicting weather in Colorado is generally difficult; however, there is one thing you can almost always bet money on: Afternoon thunderstorms from May through August are almost guaranteed on a daily basis, especially at higher elevations. Additionally, the temperature and weather conditions above 12,000 feet are almost always more severe than at lower elevations. Consequently, many people tend to underprepare for harsh weather conditions and underestimate the impact weather can have on mountaineering conditions. Some basic facts about mountains and weather:

- When wet, rocks are slippery

- When surfaces are slippery, the likelihood of falls increases

- Afternoon thunderstorms produce lightning

- Lightning tends to strike the highest object that can conduct electricity

- The higher you are in elevation, the higher your chances of being struck by lightning are

- Lightning is fatal

- Fear of being struck by lightning induces poor decision making and increases the chances of falls or poor route-finding

- Poor route finding = getting lost

- Higher elevation = colder temperatures; it is not uncommon to see snow and sleet in July at 14,000 feet

- Colder temperatures = hypothermia

Weather is undoubtedly the most dangerous aspect of mountaineering. Without proper training and preparation, climbers and hikers place themselves at substantial risk of injury and death due to weather. Weather can appear at a moment's notice, so be watchful of the clouds as you hike.

5. Dehydration: Dehydration is a fairly common occurence at higher elevation. Many hikers and climbers do not realize that the gain in elevation taxes the body even more, necessitating the need for a lot of water intake. My general rule is to drink at least 1 ounce every 15 minutes. If after 8 hours you have not drank a full Nalgene, you're probably going to experience some dehydration symptoms. The human body can only process about 16 oz. of water per hour, so drinking too much is also a problem. The fact that you are probably hiking at higher elevations increases the odds of dehydration occuring, so make sure you are drinking enough water throughout your day.

6. Avalanches: Avalanche deaths are fairly common in Colorado, unfortunately. In fact, Colorado has the most annual avalanche deaths in the United States. Frequently, mountaineers misjudge avalanche conditions or ignore warning signs and continue climbing. Avalanche conditions are not easy to detect, and there is an entire nomenclature dedicated to the subject. I do not pretend to be an expert on avalanches; however, what I do know is that one should seek out professional training and guidance before climbing in the winter and spring months in Colorado. One of the best websites which provides data on avalanche conditions in Colorado is the Colorado Avalanche Information Center (CAIC). It is a good idea to take a look at the conditions posted on that site before venturing out. Interestingly enough, people who have taken a basic avalanche class are actually more likely to perish in an avalanche than someone that has never taken a class, because they know just enough to be dangerous and tend to be overly confident in their ability to travel safely. It cannot be stressed enough that one should enroll in several avalanche courses before declaring themselves as ready to travel in avalanche-prone areas.

7. Poor Judgement: Quite possibly the most common cause of accidents and deaths in the mountaineering comumunity is poor judgement. Poor judgement is caused by ignorance, psychological factors, and just plain stupidity.

8. Physical abilities: Mountaineering is a physically demanding activity and should not be underestimated by anyone. Most beginner mountaineers are physically underprepared for the challenges of being at altitude in a foreign terrain. Even the most physically active people can be greatly challenged by the seemingly easiest of mountains. Before attempting a difficult climb, ensure that you are in peak physical condition and that your heart is operating at peak performance levels. A significant amount of individuals experience fatal heart attacks while mountaineering; therefore, it is imperitive that you have been cleared by a physician to partake in such a demanding activity. To be clear - mountaineering is extremely physically demanding - be warned!

Nasty weather moves in over Kit Carson Mountain and Crestone Peak - photo by Matt Payne

There are several relevant psychological principals that can have an impact on mountaineering safety, including groupthink, cognitive dissonance and escalation of commitment.

1.Groupthink5 is a very dangerous psychological principle coined by Irving Janus and is the primary cause of several well-known disasters such as the Challenger Shuttle Disaster, the Three Mile Island Nuclear Accident, and the Chernobyl Nuclear Disaster. Groupthink occurs when groups are highly cohesive and when they are under pressure to make a quality decision or succeed at a difficult task. Some symptoms of groupthink include:

- Illusion of invulnerability –Creates excessive optimism that encourages taking extreme risks.

- Collective rationalization – Members discount warnings and do not reconsider their assumptions.

- Belief in inherent morality – Members believe in the rightness of their cause and therefore ignore the ethical or moral consequences of their decisions.

- Stereotyped views of out-groups – Negative views of “enemy” make effective responses to conflict seem unnecessary.

- Direct pressure on dissenters – Members are under pressure not to express arguments against any of the group’s views.

- Self-censorship – Doubts and deviations from the perceived group consensus are not expressed.

- Illusion of unanimity – The majority view and judgments are assumed to be unanimous.

- Self-appointed ‘mindguards’ – Members protect the group and the leader from information that is problematic or contradictory to the group’s cohesiveness, view, and/or decisions.

For example, a group of mountaineers encounter a dangerous section of a mountain; however, none of the group members speak out about the inherent danger and the group continues on, exposing all members to a potentially hazardous event.

2. Cognitive Dissonance: Cognitive Dissonance is the feeling of uncomfortable tension which comes from holding two conflicting thoughts in the mind at the same time. For example, a mountaineer may know that their avalanche skills are only beginner at best but they also have successfully navigated many snow-fields safely. The mountaineer resolves this dissonance by rationalizing their behavior, further placing the mountaineer in danger.

3. Escalation of commitment is the phenomenon where people justify increased investment in a decision, based on the cumulative prior investment, despite new evidence suggesting that the decision was probably wrong. This manifests in mountaineering quite frequently in the following way: A Climber has hiked 14 miles and as the climber gets closer and closer to the top of the mountain, a dangerous thunderstorm builds above. The further the climber climbs, the more invested they are in reaching the top - and the more likely they are to continue climbing despite better judgement to turn around and climb to lower, safer terrain. This effect has been demonstrated in many mountaineering accidents, and I have personally been victim to this effect - fortunately I have escaped from those situations safely.

Preparing for mountaineering outtings requires good planning skills and a bit of knowledge on what to bring with you. Here are some of the key items to concern yourself with:

- If you've never been before, hook up with someone that has.

- Take a wilderness first aid course - you won't regret it.

- Get into shape. This is harder than it might sound. My personal preparation is very rudimentary, yet effective. In the winter and spring months, I walk up to 3 miles per day and at night I will do aerobic exercises. Some easy ones anyone can do include jumping jacks, walking up and down your stairs, running in place and lunges.

- Research the area where you will be going. This includes obtaining maps and understanding the proper routes as necessary.

- Pack the appropriate gear - see below for further details

- Start early! An alpine start is the best way to decrease the likelihood of exposure to afternoon thunderstorms. The general rule is to be up and down to treeline before noon. Alpine starts can also be rewarding in other ways, for example, I began my hike up Mount of the Holy Cross at 3:30 AM and was able to watch the sunrise at 13,000 ft.

- Learn how to read a TOPO map, compass, and GPS device. Do not rely on a GPS device soley unless your navigation skills are exemplary.

- Check the weather forecast for the mountain you are planning on climbing.

- Communicate with friends and family on your planned whereabouts. If you deviate from those plans, make sure someone knows about it. Let your family and friends know where you're going, how long you'll be gone, and what your anticipated routes are. These factors will be invaluable for search and rescue teams should you become injured or lost.

- Know your own limitations - if you start to feel adverse conditions, there is no shame in turning around.

Mount of the Holy Cross at sunrise - photo by Matt Payne

The following list of gear contains many of the items you will need in order to ensure a successful mountaineering trip. Additional gear would obviously be required if technical climbing was on your agenda. I've created links to my recommendations for each item type.

- Water: at least 4 oz per mile of travel - varies by individual and trips

- Food: Complex Carbohydrates, Proteins, Fats, and Salty foods are best. Some of my personal favorite food: Cheese, Nuts, Jerky, Summer Sausage, Powerbar Gel, Gatorade

- Synthetic clothing: Wear layers - I usually will wear a short-sleeved sythetic t-shirt underneath a long-sleeve synthetic base layer and some water and wind-proof pants.

- Down Jacket

- Fleece Jacket

- Nylon Shell Jacket

- Synthetic Hat (for sun)

- Warm Beanie Hat

- Gloves or mittens

- Backpack

- Map and/or GPS

- Headlamp

- First Aid Kit

- Sunglasses

- Camera

- Multitool

- Altimeter Watch

- Matches

- Sunscreen (30+ SPF)

- Climbing Helmet (depending upon mountain)

- Trekking Poles (optional)

- Gaiters (optional, depending on season)

- Broken-in mountaineering boots with gore-tex lining

- Water shoes for water crossings (if required) - I love my Chaco's.

- Ice Axe (some will argue that an ice axe should always be carried) - useful for snowfields and self-arrest during glissading

- Crampons (if needed)

- Microspikes

Matt Payne climbing the Class 4 ridge on Mount Lindsey. Photo by Ethan Beute

Here are the Ten Essesntials, as defined by The Mountaineers of Washington6:

1. Navigation (map and compass)

2. Sun protection

3. Insulation (extra clothing)

4. Illumination (flashlight/headlamp)

5. First-aid supplies

6. Fire

7. Repair kit and tools

8. Nutrition (extra food)

9. Hydration (extra water)

10. Emergency shelter

Here are some other important considerations to increase the safety of your group during your mountaineering adventure:

- Be careful not to kick rocks down on climbers below you. If you accidentily do this - please yell "ROCK!" so that those below you can prepare and take proper cover.

- Don't wander off without proper navigation skills and devices - you will get lost!

- If you are uncomfortable, hike with others and be careful to communication your expectations on traveling together vs. separated.

- Keep your eye open for dangerous wildlife. Elk, deer, bears, bighorn sheep and mountain goats can all pose hazards.

- Bring a cell phone - you never know if it will come in handy. Be courteous - don't use your cell phone on the summit unless you walk far enough away from earshot. No one wants to hear your conversation.

- Practice Leave No Trace ethics

- Be aware of your surroundings and be mindful of fellow mountaineers

Mountaineering in Colorado is dangerous; however, with the right amount of training, experience, gear, preparation and knowledge the majority of mountaineers will live to lead safe trips again and again. If you're still not convinced of the need for careful preparation and thinking, take a look at John Kirk's website on Colorado mountaineering accidents - he provides several examples of deaths and accidents in the Colorado high country. If you should have any other thoughts or questions regarding mountaineering safety, feel free to contact me. Don't become a statistic. Be safe.

References

2. Accidents in North American Mountaineering by The American Alpine Club

3. Recreational Fatalities in Colorado, 1996-1998

4. Acute Mountain Sickness: Medline Plus Medical Encylopedia

5. Janis, Irving L. (1972). Victims of Groupthink. New York: Houghton Mifflin. Janis, Irving L. (1982). Groupthink: Psychological Studies of Policy Decisions and Fiascoes. Second Edition. New York: Houghton Mifflin.