- Introduction

- Steve Gladbach - Thunder Pyramid - 6/23/2013

- Howard Scotland - Jagged Mountain - 7/11/2013

- Michael Cormier - Kit Carson Peak - 7/19/2013

- Ryan Joseph Palmer - Capitol Peak - 7/21/2013

- Paul Nahon - Longs Peak - 8/18/2013

- Corey Stewart - Lumpy Ridge - 8/22/2013

- Mark Stice - Crestone Peak - 9/17/2013

- Summary / Data / Charts / Common Themes

As many people may recall, I threw in the towel in 2013. I made a very difficult decision to stop writing about Colorado's mountaineering deaths. I was right in the middle of trying to learn the details one of the major tragedies of 2012 - Robert Jansen's death on Hagerman Peak. I was in contact with the climbers that were with him on that tragic day, a full year after the accident, and the responses I received changed the way I thought about things. I could feel the pain and anguish in their responses. I could tell, that by asking questions about the accident, I was just digging up old wounds that best lay hidden from the world to heal. I had to respect that feeling inside of me - that gut wrenching pang that I realized that my acts were causing another human being significant harm. I announced my decision and received quite interesting feedback. To my surprise, the community found value in my research and my posts, despite the sensitive and delicate nature of the topic. I even received phone calls from people I'd never met before, imploring me to continue writing. At the time, it was just too much to handle, so I put a stop to the articles.

Fast forward to 2014 - I've put significant distance between myself and the topic. I've been able to think objectively about these articles and about their value, and their potential to cause harm. I've read and re-read the post I put up on 14ers.com (linked above) and keep coming back to the same conclusion - there is value in providing this information, if done the right way. Given that conclusion, I have decided to publish the data I've collected since 2011, which is significant. I have also decided to make some significant changes in the type of information shared here. No longer will I be conducting a formal analysis, rather, a short account of known details with any obvious linkages to cause made apparent, as well as a statistical summary. It is quite difficult to walk a fine line between 1) honoring those who have died, 2) educating the general public to the dangers of the mountains and 3) showing respect to the friends and families of the deceased; however, that is my goal. The hardest part is accurately reporting the details of the story without inflicting pain on the survivors. You are committed to maintaining this delicate balance.I feel like this will strike a balance between the need for sensitivity as well as the need for information. Since my 2013 thread on 14ers.com prompted the creation of an entire new category of discussion for accident analysis, my hope is that those topics will serve that function instead. Without further ado, here are the stats for 2013...

2013 started out quite poorly with 6 avalanche deaths in the month of April. While avalanche deaths are sometimes considered mountaineering deaths, in these particular cases, I want to differentiate between mountaineering and skiing/snowboarding; therefore, I won't be officially counting these 6 deaths in the tally for 2013 mountaineering deaths. The six deaths do serve as a painful reminder to always check the avalance conditions reports through CAIC.

Through mid-July there had only been 2 deaths, and 2013 ended with 7 Colorado mountaineering deaths, one more than 2012 and 5 less than 2011. While no entity keeps official records of mountaineering deaths in Colorado, the American Alpine Club publishes its annual Accidents in North American Mountaineering (ANAM) book, which highlights every known accident and death in North America as well as providing meaningful statistics, broken down by State and type of accident. The scope and purpose of that book is for mountaineers to read about accidents and to learn from them. Through analyzing what went wrong in each situation, ANAM gives experienced and beginning mountaineers the opportunity to learn from other climbers' mistakes. From inadequate protection, clothing, or equipment to inexperience, errors in judgment, and exceeding abilities, the mistakes recorded in the book are invaluable safety lessons for all climbers.

As a reminder, the purpose of these articles here on this site is to focus more on Colorado mountaineering specifically, provide probable causes for each death, if possible, and to collect data that may prove useful in the future. It is also a goal that this website may serve as a historical reference for Colorado mountaineering accidents - at least 2010 and forward.

The philosophy is that each mistake, accident or unfortunate event has a valuable lesson attached to it. We also believe that even simple coincidences or freak accidents, where no fault can be laid upon the mountaineer, can be studied. Perhaps in reading about one of these such accidents, other climbers may decide to avoid that mountain or take extra precautions when attempting to climb it. Additionally, most of us that climb mountains do so with the knowledge that it is dangerous and that accidents can and will occur. The only thing we can do to mitigate that risk is to educate ourselves, learn from others, and prepare as much as possible. The hope is that this continued work is a small means to that end.

1. Steve Gladbach - Thunder Pyramid - 6/23/2013

Perhaps the most vexxing, painful and profound mountaineering death of 2013, if not in the past decade of Colorado mountaineering accidents was the death of Steve Gladbach on Thunder Pyramid. Steve had ascended all of the 14ers four times (many up to 15 times total) as well as over 700 13ers, and is widely considered one of the most accomplished Colorado mountaineers of his day. Steve Gladbach was an amazing and gifted man - a true friend to anyone and everyone. The impacts of his death were felt by many Colorado mountaineers, including me. This was Steve's second climb of Thunder Pyramid, and as he has done on so many occasions, was climbing it to help friends acheive their goals.

Cause

In an infamous post on 14ers.com from Steve himself, he was quoted:

"Feel free to post messages of condolence to my chlidren and family.

Do not ask for details (beyond those that a newspaper would report) so that you can "Learn" from my mistakes.

Please ,Site Administrators: if you value me at all as a person, delete such requests immediately. I have seen about 5% (That 5% often does more harm than the 95% does good) of every accident thread deteriorate into a useless guessing game designed to "analyze' the accident. In reality, it only serves to stir up feelings of guilt and loss amongst those left behind. The "lessons" learned never serve to prevent future incidents, because the armchair critics assimilate the info by convincing themselves that , "Since I take precaution "X", that will not happen to me." BS.

In every thread (and in at least one book where the author told me he didn't necessarily consider it important to interview the primary survivor), the critics boil the details down to some trite conclusion which can be filed under a particular chapter of stuff "not to do". Every time, you hear how there are no such things as "accidents"; the person performing the analysis can always explain how they would have prevented the accident. If only they could be there every time we climb!

These things are true:

Upside:

1. Training highlights preventable mistakes : PLEASE take a series of CMC or private courses designed to build skills. Repeat classes peiodically as long as you are a climber.

2. Mentorship and group participation can teach skills (Thanks, TomPierce for the fieldwork in Ruby Basin.) There is always something new to be learned from a partner.

3. GOOD books, i.e. Freedom of the Hills, written to teach actual skills, can help.

4. Time in the field teaches valuable, applicable (but not perfect) lessons.

Downside:

1. Climbing is dangerous and each climber must decide for themselves the level of risk they wish to assume.

2. Rocks move, feet slip, snow slides.

3.The exact conditions leading to an accident are never analyzed 100% correctly (witnesses are dead, traumatized, or non-existent), so the conclusions are always skewed.

4. Time in the field increases that opportunity for #1 and #2 to catch up with you!

What is useful:

1.Expressions of condolence.

2.Continued comfort and support to those left behind. An internet note and attendance at a memorial is 1% of what you COULD choose to do.

3.Take the memory of those lost with you each time you go into the field. Remembering those who have passed will do more to heighten your own awareness of potential dangers than would a critque of their errors. Remember: you've already taken courses, participated with good mentors, and read valuable books. You know what mistakes can be made. You know that you can make zero mistakes and still die.

Vigilance is the best defense and bringing along the memory of those lost partners will always heighten vigilance. Sadly, none of us are 100% vigilant. Whether an 18 y/o boy with 2 years experience or a 70 y/o legend with 50 years of climbing, you could slip on some ice and die.

If we're lucky, we might remember that and look twice before we take that next step.

ONWARDS! - Steve"

Out respect for Steve's wishes, that's all I'll post here, other than what is known to be true:

After a successful ascent of Thunder Pyramid, Steve chose to descend separately from his group and fell to his death.

2. Howard Scotland - Jagged Mountain - 7/11/2013

According to The Durango Herald, Howard Scotland, known as "WyomingBob" on 14ers.com, and owner of popular blogging site "Climbing with Bob", perished on the rugged and dangerous slopes of Jagged Mountain via a fall of 300-400 feet on July 11th, 2013. This tragedy was difficult for many to hear, especially in light of the fact that just the prior year, Howard broke his ankle on his first attempt of the same peak. This accident had an impact on me personally - I had planned to climb Jagged later in the year. I was quite distburbed by the event. I really wanted to understand, but why? So I could prepare better for my own attempt? Would it really matter? Doubtfully. Jagged is one of the most difficult mountains to climb in Colorado. It deserves a great deal of respect and preparation. It has significant exposure and a difficult Class 5 route.

Cause

I did not attempt to reach out to Howard's climbing partners, who were present during the accident; however, it is known that Howard died from a fall after he lost his footing, which is not surprising given the steep, rugged and loose terrain of Jagged Mountain.

3. Michael Cormier - Kit Carson Peak - 7/19/2013

According to the the Crestone Eagle, Michael perished from a fall while descending from the summit of Kit Carson Peak. According to other climbers that spoke with him that day, he was considering a descent via the North ridge, which is an alternate class 4 route. It would seem that from where his body was recovered, that is the route he chose to descend.

Cause

Michael's death was caused by fall during his descent of Kit Carson Peak via a non-standard route. Michael was hiking alone and had descended a different route than the one he chose to ascend. Additionally, according to others, there was a storm moving into the area, which may have contibuted in some way; however, it is unknown. Kit Carson Peak has claimed several lives in the past few years and there are common themes to all of the deaths - the climbers were all descending at the time of death and they were all either off-route or on an alternative route. I believe this is particularly important information for climbers attempting this peak as it just may serve as a reminder to either stay on the standard route or pay extra close attention to the correct route when descending.

4. Ryan Joseph Palmer - Capitol Peak - 7/21/2013

According to the NBC News, Ryan perished while descending Capitol Peak after a successful summit with friends. Instead of down-climbing the standard route across the infamous knife-edge, Ryan chose to descend via the north face of Captiol Peak, which is highly technical and quite dangerous. Capitol Peak is certainly one of the most difficult 14ers in Colorado to climb, if not the most difficult, in my opinion. The terrain on Capitol Peak is nasty - there really is not a better word for this chossy and loose monstrosity. When I climbed Capitol, we went a slightly off-route way on our ascent after crossing the knife edge and we found the terrain to be quite dangerous and scary.

Cause

Ryan's death was caused by fall during his descent of Capitol Peak on the highly technical north face of the peak. Speaking from experience, it can be tempting to descend a mountain via an alternative route; however, it comes with significant risk, especially if the climber is not aware of the route's dangers or specific pitfalls.

5. Paul Nahon - Longs Peak - 8/18/2013

According to Estes Park News, Paul Nahon died on Longs Peak while negotiating the section referred to as The Narrows, a section of narrow trail just before the summit. This particular section of the standard Keyhole route of Longs Peak is relatively safe; however, a mis-step could prove fatal, as there is significant exposure to the west of the mountain from here, as seen in this photo I took on my descent via this route back in 2009.

Cause

Paul's death was caused by a fall. It is not known if he was ascending or descending at the time of the fall. Officials with Rocky Mountain National Park said there was ice on parts of the Keyhole Route at the time of the fall, which may or may not have contributed to his fall. Longs is unfortunately the most dangerous mountain in Colorado, with over 35 deaths attributed to it. This is not because it is overly technical, rather, the sheer number of people attempting it each year is staggering. Due its location in Rocky Mountain National Park, many inexperienced people attempt Longs as their first 14er, and are met with some of the more challenging parts of the climb without the necessary mental or physical abilities needed. In Paul's case, it is not known if these factors played any role in his fall.

6. Corey Stewart - Lumpy Ridge - 8/22/2013

While this particular accident was more of a "rock climbing" accident rather than a mountaineering accident, I decided to leave it in for consideration, especially given the increase in popularity with this climbing area. According to the Denver Post, Corey Stewart perished while ascending "Batman Pinnacle" on Lumpy Ridge, located in Rocky Mountain National Park. Batman Pinnacle is a rocky crag with a popular 5.6 technical climbing route. Not much is known about the nature of the accident, and the accident itself caused quite some discussion on Mountain Project's accident forum, with similar debates as the ones that sparked my hiatus from writing these articles.

Cause

Without much available information, all that can be said about Corey's death was that it was caused by a fall during a technical climb. It is not known if it was during ascent or descent (although it can be reasonably assumed it was during ascent, since falls are not a common cause of death during roped descents), if there was gear failure (faulty rope, etc), poor protection placement, belaying mistakes, etc.

7. Mark Stice - Crestone Peak - 9/17/2013

Mark Stice, a 36-year-old man from Aurora, Colorado departed for a 5-day trip into South Colony Basin to climb Crestone Peak; however, he could have been attempting any number of peaks at the time of his assumed death, including Humboldt Peak (14,064 feet), Crestone Needle (14,197 feet), Crestone Peak (14,294 feet), Kit Carson Peak (14,165 feet) or Challenger Point (14,081 feet). Mark's body was never found and search and rescue operations ceased after 800 hours of searching.

Cause

The cause of Mark's death is unknown. He was hiking alone and left no itenarary. Stice had hiked up Humboldt Peak earlier in the year, but Search and Rescue stated that they believed he was unaware of the technical challenges he might encounter on more difficult peaks. He also was reported to descend off-route frequently, which, as seen from previous deaths in this year alone, can lead to fatal results.

Summary / Data / Charts / Common Themes

2013 was slightly more fatal than 2012, with one more death. While 2013 was not nearly as deadly as 2011 or 2010, it still marked the passing of 7 truly great people that will surely be missed by friends and loved ones. 2013 marked a return of Longs Peak to the list, and Kit Carson and Crestones made the list again. While it was somewhat surprising that there were no deaths on the Maroon Bells, Capitol Peak and the 13,932 ft. Thunder Pyramid reminded us of just how dangerous the Elk Mountains are.

My continued hope is that the data I track through this painstaking annual endevour will become useful someday for research or for education purposes. Perhaps someday an organization will use this data to fund a new education program at the Park Service or some other organization.

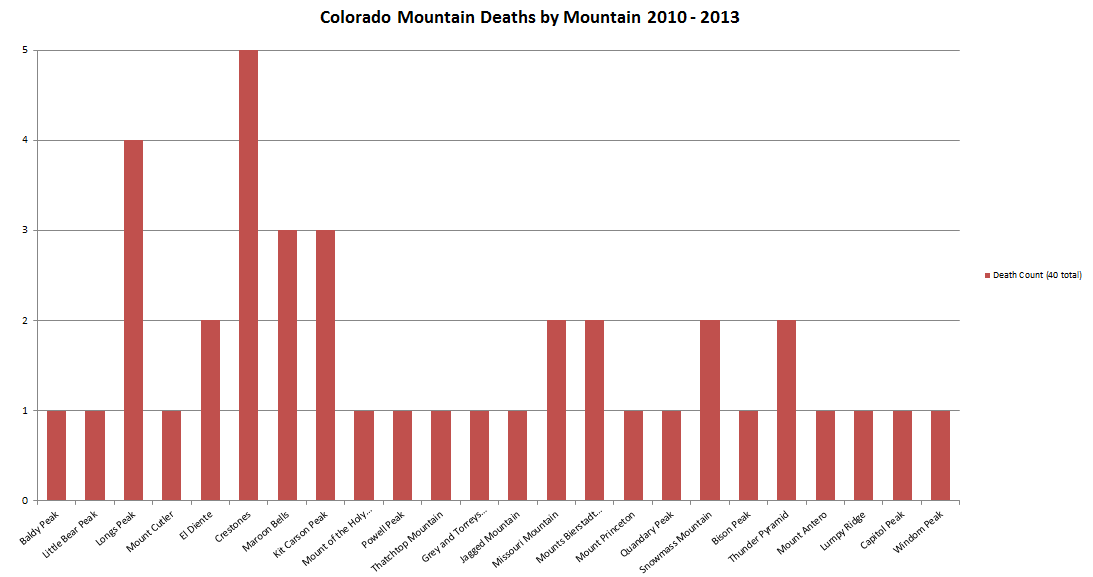

The first table I'd like to present this year is the Colorado Mountaineering Deaths by Mountain 2010 - 2013. If the table is hard to read, feel free to click on it to see a larger version.

As you can see, Longs Peak, Kit Carson Peak, the Maroon Bells, and the Crestones are the most dangerous mountains in terms of the number of accidents.

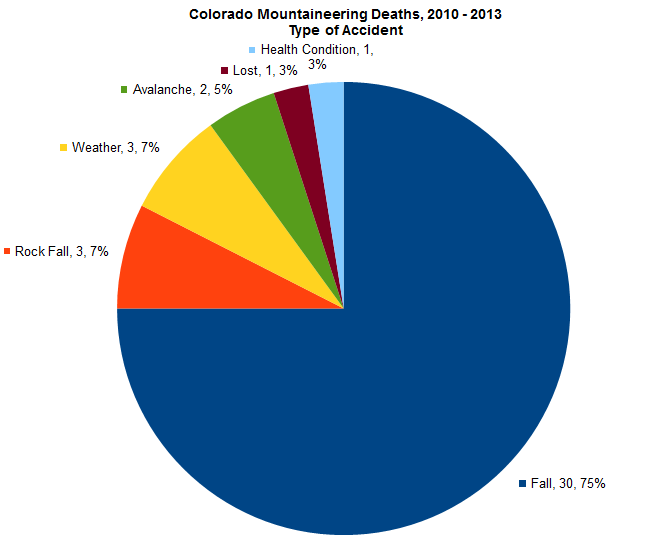

The second table I'd like to share is a count of the type of accidents:

Clearly, the leading cause of death in Colorado Mountaineering accidents from 2010 - 2013 continues to be falling.

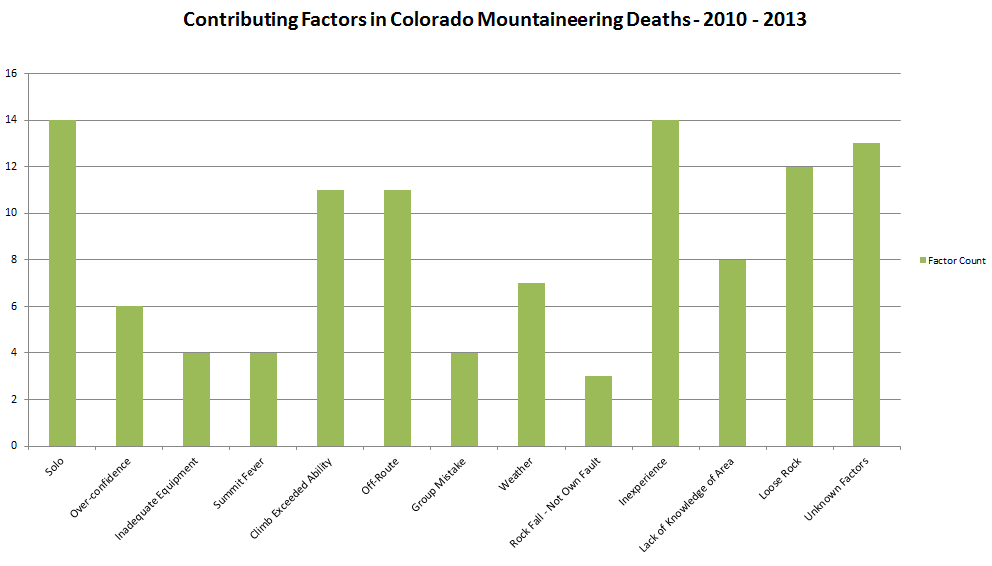

The following table shows a somewhat subjective count of the contributing factors for the Colorado Mountaineering Deaths - 2010 - 2013:

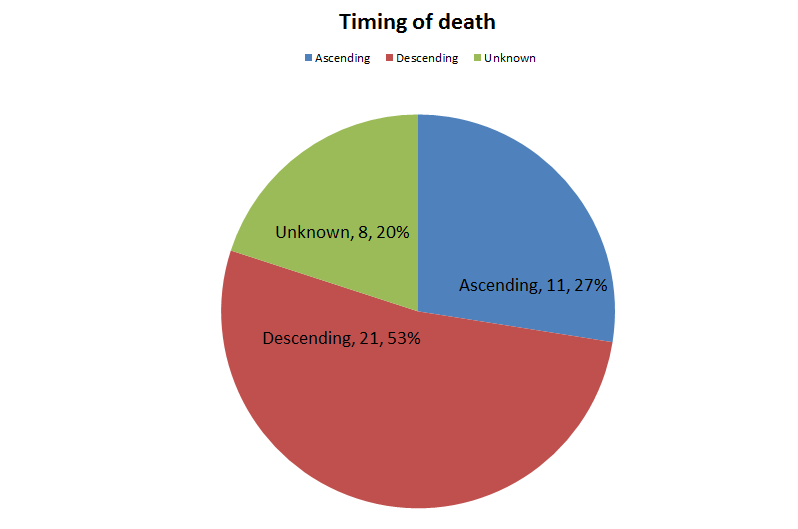

Lastly, as introduced in 2012's data, I have begun tracking if the death occurred during ascent or descent.

Hopefully this data will become more and more meaningful as the years progress, and will give educators, policy makers, and other groups some ammunition to begin targeting various interventions that would hopefully reduce the number of accidents per capita for Mountaineering Accidents.

If you have any comments or concerns about the data or ideas on other data points to start tracking, please leave a comment below. Additionally, if there are discrepancies in the information I provided above, please leave a comment so I can fix it.